Barnumbirr, also known as Banumbirr or Morning Star, is a creator-spirit in the Yolngu culture of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, who is identified as the planet Venus.[1][2] In Yolngu Dreaming mythology, she is believed to have guided the first humans, the Djanggawul sisters, to Australia.[3] After the Djanggawul sisters arrived safely near Yirrkala (at Yalangbara) in North East Arnhem Land, Barnumbirr flew across the land from east to west, creating a songline which named and created the animals, plants, and geographical features.[2][3]

| Barnumbirr (Morning Star) | |

|---|---|

Yolngu creator-spirit | |

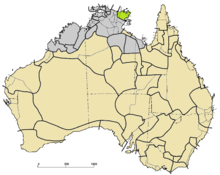

Map showing the geographical location of the Yolngu language group (Highlighted in green). | |

| Other names | Banumbirr, Morning Star |

| Affiliation | Creation, Death |

| Planet | Venus |

| Artefacts | Morning Star Pole |

| Gender | Female |

| Region | Arnhem Land, Australia |

| Ethnic group | Yolngu |

| Festivals | Morning Star Ceremony |

Songlines were an important navigational tool for Aboriginal people.[4] The route that Barnumbirr flew above northern Australia became a songline that spans multiple language groups and was therefore useful for travelling Yolngu and their neighbours.[5][4] There is a growing body of research suggesting that this song-line through the Northern Territory/Western Australia and others tracing paths in NSW and Queensland have formed part of Australia’s network of motorways.[6][4][5]

Barnumbirr has a strong association with death in Yolngu culture.[2] The "Morning Star Ceremony" corresponds with the rising of Barnumbirr and is a time when living Yolngu, with the help of Barnumbirr and the "Morning Star Pole", can communicate with their ancestors on Bralgu (var. Baralku), their final resting place.[3][2]

Role in creation

editBarnumbirr as a Morning Star is a creator spirit in Yolngu culture.[2] Her story is part of the Dhuwa moiety.[7] Yolngu songlines depict Barnumbirr guiding the Djanggawul sisters as they row a canoe from the mythical island of Bralgu (the home of Wangarr, the Great Creator Spirit) to discover Australia[3] and bring Madayin Law to the Dhuwa people.[8] Once the sisters found land near Yirrkala in North East Arnhem Land,[3] Barnumbirr is believed to have continued flying eastward creating a song-line which includes descriptions of flora, fauna, geographical features and clan borders.[2] Barnumbirr’s songline therefore formed the basis of Madayin Law and the Yolngu understanding of the land.[2][8]

Relationship with death

editBarnumbirr has strong associations with death for Yolngu people.[1][2] The rising of Barnumbirr in the sky before sunrise is a time when the Yolngu conduct the "Morning Star Ceremony".[2] As Venus becomes visible in the early hours before dawn, the Yolngu say that she draws behind her a rope that is connected to the island of Bralgu.[2] Along this rope, with the aid of a richly decorated "Morning Star Pole", Yolngu people are able to release the spirits of their dead and communicate with their ancestors.[9][1]

Research[2] suggests that this light is likely zodiacal light, caused by extraterrestrial dust reflecting light from the solar system. This ‘rope’ is important in Yolngu mythology because it prevents Barnumbirr from straying too far from Bralgu and facilitates communication between dead and living people.[1][2][9]

The Morning Star Ceremony

editThe Morning Star Ceremony is a mortuary ceremony of the Dhuwa moiety.[7][2] In Dhuwa mythology, the Wangarr (Yolngu ancestors) perform the Morning Star ceremony every night of Venus’ synodic period.[10] In the real world, the Morning Star Ceremony is an important part of the funeral process for a small number of Yolngu clans.[2] The ceremony begins at dusk and continues through the night, reaching a climax when Barnumbirr rises trailing a rope of light to connect with Bralgu.[2] When Barnumbirr rises, the spirits of those who have recently died are released with the help of the Ceremony to Wangarr, the spirit-world.[10]

Planning the Morning Star Ceremony

editDue to its scale and importance, the "Morning Star Ceremony" requires a significant level of planning.[1] It occurs over the course of the night prior the first rising of Venus after a synodic period of approximately 584 days.[11] Venus can then be seen as a Morning Star for approximately 263 days.[11] The Yolngu people count the days of Venus’ synodic period to track the motion of Venus and plan the Morning Star Ceremony[1][12]

The Morning Star Pole

editThe Morning Star Pole is a decorated ceremonial piece used in the Morning Star Ceremony.[2] It is used to communicate with ancestors on Bralgu and is designed to depict Barnumbirr, its tail of zodiacal light and neighbouring celestial bodies.[2][12] Each Morning Star Pole is unique to individual craftsmen and clans and therefore unique in appearance (Gurriwiwi, 2009).[citation needed]

Attached to the top of the pole are feathers from a variety of birds which represent the Morning Star itself (Norris, 2016; Gurriwiwi, 2009). The pole is coloured with traditional patterns in ochre paint and together are a representation of the artist and their surrounding environment.[13] Pandanus strings attach more feathers to the pole.[2] These strings represent the string of light that attaches Barnumbirr to Bralgu[12] as well as neighbouring stars and planets.[2]

Public interest in Morning Star poles

editMorning Star poles have attracted attention from art galleries and collectors across the world.[14] Poles have been exhibited in a number of major Australian galleries and museums including QAGOMA,[15] the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia,[16] the Art Gallery of NSW[17] and the Australian National Maritime Museum.[18] Gali Yalkarriwuy Gurruwiwi is a Yolngu man from Elcho Island in Arnhem Land. He is a Morning Star custodian, maker and artist of Morning Star poles which have been displayed in galleries across the world.[19] Gurriwiwi expresses a desire to use his art as a way bring people together and teach them about Yolngu culture.[20][21] This desire to share indigenous culture with non-aboriginal people via Morning Star Poles is also shared by fellow Arnhem Land artist Bob Burruwal.[16]

Venus in other Australian Indigenous cultures

editVenus is the third brightest object in the night sky[12] and because of this there are numerous cultural interpretations of Venus as a Morning and Evening Star across Australia’s Indigenous groups.[12] The literature is sparse on the details of many of these interpretations,[1][2][5][9][12][22] and in some cases cultural limitations prevent information from being shared.[2][22] There are, however, relatively detailed recounts of the Euahlayi and Kamilaroi,[6][22] Arrernte[12][23] and Queensland Gulf Country people’s[12][24][25] interpretations.

Kamilaroi and Euahlayi

editThe Kamilaroi and Euahlayi peoples of Northern New South Wales interpret Venus as a morning star differently to the Yolngu but it shares similar significance.[22] The story of the Eagle-hawk (Muliyan) is recounted in Reed[24] Fuller[22] and Hamacher & Banks.[12] The eagle-hawk once lived in a large Yarran tree and hunted people for food near the Barwon River. One day, a group of men set out after him to avenge his killing of their people. The men set fire to the tree and killed Muliyan. The eagle-hawk then ascended into the sky as Muliyangah, the morning star. Euahlayi/Kamilaroi people interpret Muliyangah as the eyes of Baayami (Baiame) watching over the earth during the night.[22]

Due to Baayami’s cultural significance, Kamilaroi/Euahlayi people also place great importance on a Morning Star Ceremony but cultural sensitivities prevent much detail from being revealed in the literature.[22] Fuller’s research[22] does explain, however, that Venus rising as an evening star is a sign to light a sacred fire. This fire is re-lit every night until Venus rises as a Morning Star and the flame is extinguished. Like the Yolngu version this ceremony also includes the use of a wooden pole, but in this case it is held horizontally as a symbol of connection between dark and light peoples (the two moieties of the Kamilaroi/Euahlayi), and the unity of marriage.[22] The Euahlayi/Kamilaroi also require an understanding of the celestial movements of Venus. The literature is unclear, however, on how Euahlayi/Kamilaroi elders predict the date Venus rises.[22]

Arrernte

editVenus as a morning and evening star are a central component of the Arrernte interpretation of Tnorala. Tnorala is a 5-kilometre-wide, 250-metre-tall ring-shaped mountain range 160 km (99 mi) west of Alice Springs.[12] Arrernte people believe that in the creation period, a group of women took the form of stars and danced the Corroboree in the Milky Way.[12][23] As they danced, one of the women dropped a baby which then fell to earth and formed the indent that can be seen in the ring-shaped mountain range. The baby’s parents, the morning star (father) and evening star (mother), continue to take turns looking for their baby.Arrernte parents warn their children not to stare at the morning or evening stars because the baby’s parents may mistake a staring child for their own and take them away.[12][23]

North Queensland Gulf Country Aboriginal peoples

editSimilarities can be found between creator role of Barnumbirr in Yolngu culture, and the Morning Star as a creator spirit in North Queensland's Gulf Country Dreaming. Gulf country Aboriginal peoples believed that two brothers, the moon (older) and the morning star (younger) travel across the landscape in the creation period, using a boomerang to create features of the landscape such as valleys, hills and seas.[12][24][25]

Further interpretations

editSonglines and mapping

editFor Aboriginal Australians, songlines (also called "Dreaming Tracks") are an oral map of the landscape, setting out trading routes,[26] and often connecting sacred sites.[5] Song-lines on the land are often mirrored, or mirrors of, "paths" connecting stars and planets in the sky.[4] Star maps are also play an important role as mnemonics to aid in the memory of songlines.[5]

The path that Barnumbirr is believed to have travelled from west to east across northern Australia is recounted in a songline that tracks a navigable route through the landscape.[2] Mountains, waterholes and clan boundaries are mentioned throughout the song and it therefore became an important navigational tool for travelling Yolngu and their neighbours.[1][4][5]

Songlines and Australia's highway network

editThere is new research[4][5][6] suggesting that these song-lines form the basic route of significant sections of Australia’s highway network. Colonial explorers and mappers used Indigenous peoples as guides, who navigated using their star maps when travelling through the land.[4] It is hypothesised that these Dreaming tracks were then solidified by the construction and subsequent upgrade of modern roads.[4][5] By matching star maps from Euahlayi and Kamilaroi cultures with maps of modern Australian roads in northern NSW, Fuller[4] finds strong similarities. Harney and Wositsky[27] and Harney & Norris[5] also argue that the Barnumbirr songline sets a course similar to that of the Victoria Highway across the Northern Territory:

They call it the Victorian Highway now, but it was never the Victorian Highway at all – it was just the original Aboriginal walking track right through Arnhem Land.[27]

The historical evidence surrounding this concept is sparse but more recent work is uncovering the significance of song-lines (related to Barnumbirr and otherwise) in forming the basis for modern Australian roads.

In the arts and media

editDance

editBanula Marika collaborated with founder of the Australian Dance Theatre, choreographer Elizabeth Cameron Dalman, in a dance performance entitled Morning Star (2012–3). Marika is custodian of the Morning Star story,[28] and served as cultural consultant on the work. The Mirramu Dance Company performed Morning Star in March 2013 at the James O. Fairfax Theatre, National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.[29]

Film

editA forthcoming documentary film entitled Morning Star, about renowned elder and master maker and player of the yidaki, Djalu Gurruwiwi, is as of January 2021[update] in the post-production phase.[30][31]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Norris, Ray P.; Hamacher, Duane W. (2009). "The Astronomy of Aboriginal Australia". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5 (S260): 39–47. arXiv:0906.0155. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002122. ISSN 1743-9213.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Norris, Ray P. (2016). "Dawes Review 5: Australian Aboriginal Astronomy and Navigation". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. 33: e039. arXiv:1607.02215. Bibcode:2016PASA...33...39N. doi:10.1017/pasa.2016.25. ISSN 1323-3580.

- ^ a b c d e Berndt, Ronald M. (Ronald Murray) (5 February 2015). Djanggawul : an aboriginal religious cult of north-eastern Arnhem Land. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-138-86198-5. OCLC 941876435.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fuller, Robert S. (6 April 2016). "How ancient Aboriginal star maps have shaped Australia's highway network". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harney, Bill; Norris, Ray (2014). "Song-lines and Navigation in Wardaman and Other Aboriginal Cultures". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 17: 141–148.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Robert; Trudgett, Michelle; Norris, Ray; Anderson, Michael (2014). "Starmaps and Travelling to Ceremonies: The Euahlayi People and their use of the night sky". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 17 (2): 149–160. arXiv:1406.7456. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2014.02.02. S2CID 53403053.

- ^ a b Hutcherson, Gillian (1995). Djalkiri Wanga: The Land is My Foundation. Western Australia: Berndt Museum of Anthropology. ISBN 0864224214.

- ^ a b Gondarra, D. (2011). The Law and Justice within Indigenous Communities. Presentation, Darwin, NT

- ^ a b c Allen, L. (1976). Time Before Morning: Art and Myth of Aboriginal Australians. Adelaide: Rigby.

- ^ a b ABC Education. (2009). Morning Star Poles tell an artistic story [Video].

- ^ a b The Venus Transit. (2004). European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 24 April 2020, from https://www.eso.org/public/outreach/eduoff/vt-2004/Education/edu1app4.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hamacher, Duane W.; Banks, Kirsten (25 February 2019), "The Planets in Aboriginal Australia", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190647926.013.53, ISBN 978-0-19-064792-6, retrieved 17 May 2020

- ^ Gurruwiwi, G. (2009). Morning Star Poles tell an artistic story [TV]. Elcho Island.

- ^ Rothwell, Nicolas (2010). "Yalkarriwuy's morning star on the rise". The Australian.

- ^ Banumbirr (Morning Star Poles), 2017, Exhibition, QAGOMA, Access: https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/goma10hub/artists/banumbirr-morning-star-poles

- ^ a b Burruwal, B. (2016). Buya Male. Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Access: https://www.mca.com.au/artists-works/works/2016.32/

- ^ Djarrankuykuy, B (1948). Banumbirr, Sydney: Art Gallery of NSW. Access: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/9283/

- ^ Banumbirr: Morning Star Poles from Arnhem Land, NT, Australia, retrieved 17 May 2020

- ^ Hood Museum of Art (2012). Crossing cultures : the Owen and Wagner collection of contemporary aboriginal Australian art at the Hood Museum of Art. Gilchrist, Stephen, Butler, Sally. Hanover, New Hampshire. ISBN 978-0-944722-44-2. OCLC 785870480.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gurruwiwi, G. (2009). Morning Star Poles tell an artistic story [TV]. Elcho Island.

- ^ Millar, Paul (2008). "An art passed from father to son captures life in poles (and $25,000)".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fuller, R (2015). The astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi peoples and their neighbours (MPhil thesis). Macquarie University.

- ^ a b c Thornton, W., 2007. Tnorala - Baby Falling. (Video) Canberra, Ronin Films. Produced by the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, Alice Springs.

- ^ a b c Reed, Alexander (1965). Myths and legends of Australia. Sydney, Australia: Reed New Holland. ISBN 058907041X.

- ^ a b Hulley, Charles E., 1928- (1996). Dreamtime moon : aboriginal myths of the moon. Roberts, Ainslie. Chatswood, NSW: Reed Books. ISBN 0-7301-0491-5. OCLC 37156218.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mulvaney, J., & Kamminga, J. (1999). Prehistory of Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin

- ^ a b Harney, Bill; Wositsky, Jan (1999). Born under the paperbark tree: a man's life. Sydney: ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-0514-8. OCLC 38410566.

- ^ Kingma, Jennifer (10 March 2012). "A passion for dance". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Potter, Michelle (21 March 2013). "Morning Star. Mirramu Dance Company". Michelle Potter... On Dance. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "About Morning Star". Morning Star Documentary. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "What is Morning Star?". Morning Star Documentary. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

External links

editMorning Star Ceremony at Australian National Maritime Museum in 2002 on YouTube. Published by Bandigan Arts (2014).