Infrared spectroscopy (IR spectroscopy or vibrational spectroscopy) is the measurement of the interaction of infrared radiation with matter by absorption, emission, or reflection. It is used to study and identify chemical substances or functional groups in solid, liquid, or gaseous forms. It can be used to characterize new materials or identify and verify known and unknown samples. The method or technique of infrared spectroscopy is conducted with an instrument called an infrared spectrometer (or spectrophotometer) which produces an infrared spectrum. An IR spectrum can be visualized in a graph of infrared light absorbance (or transmittance) on the vertical axis vs. frequency, wavenumber or wavelength on the horizontal axis. Typical units of wavenumber used in IR spectra are reciprocal centimeters, with the symbol cm−1. Units of IR wavelength are commonly given in micrometers (formerly called "microns"), symbol μm, which are related to the wavenumber in a reciprocal way. A common laboratory instrument that uses this technique is a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer. Two-dimensional IR is also possible as discussed below.

The infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum is usually divided into three regions; the near-, mid- and far- infrared, named for their relation to the visible spectrum. The higher-energy near-IR, approximately 14,000–4,000 cm−1 (0.7–2.5 μm wavelength) can excite overtone or combination modes of molecular vibrations. The mid-infrared, approximately 4,000–400 cm−1 (2.5–25 μm) is generally used to study the fundamental vibrations and associated rotational–vibrational structure. The far-infrared, approximately 400–10 cm−1 (25–1,000 μm) has low energy and may be used for rotational spectroscopy and low frequency vibrations. The region from 2–130 cm−1, bordering the microwave region, is considered the terahertz region and may probe intermolecular vibrations.[1] The names and classifications of these subregions are conventions, and are only loosely based on the relative molecular or electromagnetic properties.

Uses and applications

editInfrared spectroscopy is a simple and reliable technique widely used in both organic and inorganic chemistry, in research and industry. and products during the catalytic reaction. It is used in quality control, dynamic measurement, and monitoring applications such as the long-term unattended measurement of CO2 concentrations in greenhouses and growth chambers by infrared gas analyzers.[citation needed]

It is also used in forensic analysis in both criminal and civil cases, for example in identifying polymer degradation. It can be used in determining the blood alcohol content of a suspected drunk driver.

IR spectroscopy has been used in identification of pigments in paintings[2] and other art objects[3] such as illuminated manuscripts.[4]

Infrared spectroscopy is also useful in measuring the degree of polymerization in polymer manufacture. Changes in the character or quantity of a particular bond are assessed by measuring at a specific frequency over time. Instruments can routinely record many spectra per second in situ, providing insights into reaction mechanism (e.g., detection of intermediates) and reaction progress.[citation needed]

Infrared spectroscopy is utilized in the field of semiconductor microelectronics:[5] for example, infrared spectroscopy can be applied to semiconductors like silicon, gallium arsenide, gallium nitride, zinc selenide, amorphous silicon, silicon nitride, etc.

Another important application of infrared spectroscopy is in the food industry to measure the concentration of various compounds in different food products.[6][7]

Infrared spectroscopy is also used in gas leak detection devices such as the DP-IR and EyeCGAs.[8] These devices detect hydrocarbon gas leaks in the transportation of natural gas and crude oil.

Infrared spectroscopy is an important analysis method in the recycling process of household waste plastics, and a convenient stand-off method to sort plastic of different polymers (PET, HDPE, ...).[9]

Other developments include a miniature IR-spectrometer that's linked to a cloud based database and suitable for personal everyday use,[10] and NIR-spectroscopic chips[11] that can be embedded in smartphones and various gadgets.

In catalysis research it is a very useful tool to characterize the catalyst,[12][13][14] as well as to detect intermediates[15]

Infrared spectroscopy coupled with machine learning and artificial intelligence also has potential for rapid, accurate and non-invasive sensing of bacteria.[16] The complex chemical composition of bacteria, including nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates and fatty acids, results in high-dimensional datasets where the essential features are effectively hidden under the total spectrum. Extraction of the essential features therefore requires advanced statistical methods such as machine learning and deep-neural networks. The potential of this technique for bacteria classification have been demonstrated for differentiation at the genus,[17] species[18] and serotype[19] taxonomic levels, and it has also been shown promising for antimicrobial susceptibility testing,[20][21][22] which is important for many clinical settings where faster susceptibility testing would decrease unnecessary blind-treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The main limitation of this technique for clinical applications is the high sensitivity to technical equipment and sample preparation techniques, which makes it difficult to construct large-scale databases. Attempts in this direction have however been made by Bruker with the IR Biotyper for food microbiology.[23]

Theory

editInfrared spectroscopy exploits the fact that molecules absorb frequencies that are characteristic of their structure. These absorptions occur at resonant frequencies, i.e. the frequency of the absorbed radiation matches the vibrational frequency. The energies are affected by the shape of the molecular potential energy surfaces, the masses of the atoms, and the associated vibronic coupling.[24]

In particular, in the Born–Oppenheimer and harmonic approximations (i.e. when the molecular Hamiltonian corresponding to the electronic ground state can be approximated by a harmonic oscillator in the neighbourhood of the equilibrium molecular geometry), the resonant frequencies are associated with the normal modes of vibration corresponding to the molecular electronic ground state potential energy surface. Thus, it depends on both the nature of the bonds and the mass of the atoms that are involved. Using the Schrödinger equation leads to the selection rule for the vibrational quantum number in the system undergoing vibrational changes:

The compression and extension of a bond may be likened to the behaviour of a spring, but real molecules are hardly perfectly elastic in nature. If a bond between atoms is stretched, for instance, there comes a point at which the bond breaks and the molecule dissociates into atoms. Thus real molecules deviate from perfect harmonic motion and their molecular vibrational motion is anharmonic. An empirical expression that fits the energy curve of a diatomic molecule undergoing anharmonic extension and compression to a good approximation was derived by P.M. Morse, and is called the Morse function. Using the Schrödinger equation leads to the selection rule for the system undergoing vibrational changes :

Number of vibrational modes

editIn order for a vibrational mode in a sample to be "IR active", it must be associated with changes in the molecular dipole moment. A permanent dipole is not necessary, as the rule requires only a change in dipole moment.[26]

A molecule can vibrate in many ways, and each way is called a vibrational mode. For molecules with N number of atoms, geometrically linear molecules have 3N – 5 degrees of vibrational modes, whereas nonlinear molecules have 3N – 6 degrees of vibrational modes (also called vibrational degrees of freedom). As examples linear carbon dioxide (CO2) has 3 × 3 – 5 = 4, while non-linear water (H2O), has only 3 × 3 – 6 = 3.[27]

Simple diatomic molecules have only one bond and only one vibrational band. If the molecule is symmetrical, e.g. N2, the band is not observed in the IR spectrum, but only in the Raman spectrum. Asymmetrical diatomic molecules, e.g. carbon monoxide (CO), absorb in the IR spectrum. More complex molecules have many bonds, and their vibrational spectra are correspondingly more complex, i.e. big molecules have many peaks in their IR spectra.

The atoms in a CH2X2 group, commonly found in organic compounds and where X can represent any other atom, can vibrate in nine different ways. Six of these vibrations involve only the CH2 portion: two stretching modes (ν): symmetric (νs) and antisymmetric (νas); and four bending modes: scissoring (δ), rocking (ρ), wagging (ω) and twisting (τ), as shown below. Structures that do not have the two additional X groups attached have fewer modes because some modes are defined by specific relationships to those other attached groups. For example, in water, the rocking, wagging, and twisting modes do not exist because these types of motions of the H atoms represent simple rotation of the whole molecule rather than vibrations within it. In case of more complex molecules, out-of-plane (γ) vibrational modes can be also present.[28]

Symmetry Direction |

Symmetric | Antisymmetric |

|---|---|---|

| Radial | Symmetric stretching (νs) |

Antisymmetric stretching (νas) |

| Latitudinal | Scissoring (δ) |

Rocking (ρ) |

| Longitudinal | Wagging (ω) |

Twisting (τ) |

These figures do not represent the "recoil" of the C atoms, which, though necessarily present to balance the overall movements of the molecule, are much smaller than the movements of the lighter H atoms.

The simplest and most important or fundamental IR bands arise from the excitations of normal modes, the simplest distortions of the molecule, from the ground state with vibrational quantum number v = 0 to the first excited state with vibrational quantum number v = 1. In some cases, overtone bands are observed. An overtone band arises from the absorption of a photon leading to a direct transition from the ground state to the second excited vibrational state (v = 2). Such a band appears at approximately twice the energy of the fundamental band for the same normal mode. Some excitations, so-called combination modes, involve simultaneous excitation of more than one normal mode. The phenomenon of Fermi resonance can arise when two modes are similar in energy; Fermi resonance results in an unexpected shift in energy and intensity of the bands etc.[citation needed]

Practical IR spectroscopy

editThe infrared spectrum of a sample is recorded by passing a beam of infrared light through the sample. When the frequency of the IR matches the vibrational frequency of a bond or collection of bonds, absorption occurs. Examination of the transmitted light reveals how much energy was absorbed at each frequency (or wavelength). This measurement can be achieved by scanning the wavelength range using a monochromator. Alternatively, the entire wavelength range is measured using a Fourier transform instrument and then a transmittance or absorbance spectrum is extracted.

This technique is commonly used for analyzing samples with covalent bonds. The number of bands roughly correlates with symmetry and molecular complexity.

A variety of devices are used to hold the sample in the path of the IR beam These devices are selected on the basis of their transparency in the region of interest and their resilience toward the sample.

| material | transparency range (cm-1) | comment |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride | 5000-650 | attacked (dissolved) by water, small alcohols, some amines |

| Calcium fluoride | 4200-1300 | insoluble in most solvents |

| Silver chloride | 5000-500 | attacked (dissolved) by amines, organosulfur compounds |

Sample preparation

editGas samples

editGaseous samples require a sample cell with a long pathlength to compensate for the diluteness. The pathlength of the sample cell depends on the concentration of the compound of interest. A simple glass tube with length of 5 to 10 cm equipped with infrared-transparent windows at both ends of the tube can be used for concentrations down to several hundred ppm. Sample gas concentrations well below ppm can be measured with a White's cell in which the infrared light is guided with mirrors to travel through the gas. White's cells are available with optical pathlength starting from 0.5 m up to hundred meters.[citation needed]

Liquid samples

editLiquid samples can be sandwiched between two plates of a salt (commonly sodium chloride, or common salt, although a number of other salts such as potassium bromide or calcium fluoride are also used).[30] The plates are transparent to the infrared light and do not introduce any lines onto the spectra. With increasing technology in computer filtering and manipulation of the results, samples in solution can now be measured accurately (water produces a broad absorbance across the range of interest, and thus renders the spectra unreadable without this computer treatment).[citation needed]

Solid samples

editSolid samples can be prepared in a variety of ways. One common method is to crush the sample with an oily mulling agent (usually mineral oil Nujol). A thin film of the mull is applied onto salt plates and measured. The second method is to grind a quantity of the sample with a specially purified salt (usually potassium bromide) finely (to remove scattering effects from large crystals). This powder mixture is then pressed in a mechanical press to form a translucent pellet through which the beam of the spectrometer can pass.[30] A third technique is the "cast film" technique, which is used mainly for polymeric materials. The sample is first dissolved in a suitable, non-hygroscopic solvent. A drop of this solution is deposited on the surface of a KBr or NaCl cell. The solution is then evaporated to dryness and the film formed on the cell is analysed directly. Care is important to ensure that the film is not too thick otherwise light cannot pass through. This technique is suitable for qualitative analysis. The final method is to use microtomy to cut a thin (20–100 μm) film from a solid sample. This is one of the most important ways of analysing failed plastic products for example because the integrity of the solid is preserved.[citation needed]

In photoacoustic spectroscopy the need for sample treatment is minimal. The sample, liquid or solid, is placed into the sample cup which is inserted into the photoacoustic cell which is then sealed for the measurement. The sample may be one solid piece, powder or basically in any form for the measurement. For example, a piece of rock can be inserted into the sample cup and the spectrum measured from it.[citation needed]

A useful way of analyzing solid samples without the need for cutting samples uses ATR or attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy. Using this approach, samples are pressed against the face of a single crystal. The infrared radiation passes through the crystal and only interacts with the sample at the interface between the two materials.[citation needed]

Comparing to a reference

editIt is typical to record spectrum of both the sample and a "reference". This step controls for a number of variables, e.g. infrared detector, which may affect the spectrum. The reference measurement makes it possible to eliminate the instrument influence.[citation needed]

The appropriate "reference" depends on the measurement and its goal. The simplest reference measurement is to simply remove the sample (replacing it by air). However, sometimes a different reference is more useful. For example, if the sample is a dilute solute dissolved in water in a beaker, then a good reference measurement might be to measure pure water in the same beaker. Then the reference measurement would cancel out not only all the instrumental properties (like what light source is used), but also the light-absorbing and light-reflecting properties of the water and beaker, and the final result would just show the properties of the solute (at least approximately).[citation needed]

A common way to compare to a reference is sequentially: first measure the reference, then replace the reference by the sample and measure the sample. This technique is not perfectly reliable; if the infrared lamp is a bit brighter during the reference measurement, then a bit dimmer during the sample measurement, the measurement will be distorted. More elaborate methods, such as a "two-beam" setup (see figure), can correct for these types of effects to give very accurate results. The Standard addition method can be used to statistically cancel these errors.

Nevertheless, among different absorption-based techniques which are used for gaseous species detection, Cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) can be used as a calibration-free method. The fact that CRDS is based on the measurements of photon life-times (and not the laser intensity) makes it needless for any calibration and comparison with a reference [31]

Some instruments also automatically identify the substance being measured from a store of thousands of reference spectra held in storage.

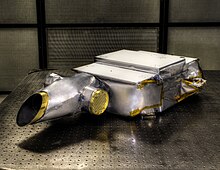

FTIR

editFourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a measurement technique that allows one to record infrared spectra. Infrared light is guided through an interferometer and then through the sample (or vice versa). A moving mirror inside the apparatus alters the distribution of infrared light that passes through the interferometer. The signal directly recorded, called an "interferogram", represents light output as a function of mirror position. A data-processing technique called Fourier transform turns this raw data into the desired result (the sample's spectrum): light output as a function of infrared wavelength (or equivalently, wavenumber). As described above, the sample's spectrum is always compared to a reference.[citation needed]

An alternate method for acquiring spectra is the "dispersive" or "scanning monochromator" method. In this approach, the sample is irradiated sequentially with various single wavelengths. The dispersive method is more common in UV-Vis spectroscopy, but is less practical in the infrared than the FTIR method. One reason that FTIR is favored is called "Fellgett's advantage" or the "multiplex advantage": The information at all frequencies is collected simultaneously, improving both speed and signal-to-noise ratio. Another is called "Jacquinot's Throughput Advantage": A dispersive measurement requires detecting much lower light levels than an FTIR measurement.[32] There are other advantages, as well as some disadvantages,[32] but virtually all modern infrared spectrometers are FTIR instruments.

Infrared microscopy

editVarious forms of infrared microscopy exist. These include IR versions of sub-diffraction microscopy[33] such as IR NSOM,[34] photothermal microspectroscopy, Nano-FTIR and atomic force microscope based infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR).

Other methods in molecular vibrational spectroscopy

editInfrared spectroscopy is not the only method of studying molecular vibrational spectra. Raman spectroscopy involves an inelastic scattering process in which only part of the energy of an incident photon is absorbed by the molecule, and the remaining part is scattered and detected. The energy difference corresponds to absorbed vibrational energy.[citation needed]

The selection rules for infrared and for Raman spectroscopy are different at least for some molecular symmetries, so that the two methods are complementary in that they observe vibrations of different symmetries.[citation needed]

Another method is electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), in which the energy absorbed is provided by an inelastically scattered electron rather than a photon. This method is useful for studying vibrations of molecules adsorbed on a solid surface.

Recently, high-resolution EELS (HREELS) has emerged as a technique for performing vibrational spectroscopy in a transmission electron microscope (TEM).[35] In combination with the high spatial resolution of the TEM, unprecedented experiments have been performed, such as nano-scale temperature measurements,[36][37] mapping of isotopically labeled molecules,[38] mapping of phonon modes in position- and momentum-space,[39][40] vibrational surface and bulk mode mapping on nanocubes,[41] and investigations of polariton modes in van der Waals crystals.[42] Analysis of vibrational modes that are IR-inactive but appear in inelastic neutron scattering is also possible at high spatial resolution using EELS.[43] Although the spatial resolution of HREELs is very high, the bands are extremely broad compared to other techniques.[35]

Computational infrared microscopy

editBy using computer simulations and normal mode analysis it is possible to calculate theoretical frequencies of molecules.[44]

Absorption bands

editIR spectroscopy is often used to identify structures because functional groups give rise to characteristic bands both in terms of intensity and position (frequency). The positions of these bands are summarized in correlation tables as shown below.

Regions

editA spectrograph is often interpreted as having two regions.[45]

- functional group region

In the functional region there are one to a few troughs per functional group.[45]

- fingerprint region

In the fingerprint region there are many troughs which form an intricate pattern which can be used like a fingerprint to determine the compound.[45]

Badger's rule

editFor many kinds of samples, the assignments are known, i.e. which bond deformation(s) are associated with which frequency. In such cases further information can be gleaned about the strength on a bond, relying on the empirical guideline called Badger's rule. Originally published by Richard McLean Badger in 1934,[46] this rule states that the strength of a bond (in terms of force constant) correlates with the bond length. That is, increase in bond strength leads to corresponding bond shortening and vice versa.

Isotope effects

editThe different isotopes in a particular species may exhibit different fine details in infrared spectroscopy. For example, the O–O stretching frequency (in reciprocal centimeters) of oxyhemocyanin is experimentally determined to be 832 and 788 cm−1 for ν(16O–16O) and ν(18O–18O), respectively.

By considering the O–O bond as a spring, the frequency of absorbance can be calculated as a wavenumber [= frequency/(speed of light)]

where k is the spring constant for the bond, c is the speed of light, and μ is the reduced mass of the A–B system:

( is the mass of atom ).

The reduced masses for 16O–16O and 18O–18O can be approximated as 8 and 9 respectively. Thus

The effect of isotopes, both on the vibration and the decay dynamics, has been found to be stronger than previously thought. In some systems, such as silicon and germanium, the decay of the anti-symmetric stretch mode of interstitial oxygen involves the symmetric stretch mode with a strong isotope dependence. For example, it was shown that for a natural silicon sample, the lifetime of the anti-symmetric vibration is 11.4 ps. When the isotope of one of the silicon atoms is increased to 29Si, the lifetime increases to 19 ps. In similar manner, when the silicon atom is changed to 30Si, the lifetime becomes 27 ps.[47]

Two-dimensional IR

editTwo-dimensional infrared correlation spectroscopy analysis combines multiple samples of infrared spectra to reveal more complex properties. By extending the spectral information of a perturbed sample, spectral analysis is simplified and resolution is enhanced. The 2D synchronous and 2D asynchronous spectra represent a graphical overview of the spectral changes due to a perturbation (such as a changing concentration or changing temperature) as well as the relationship between the spectral changes at two different wavenumbers.[citation needed]

Nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy[48][49] is the infrared version of correlation spectroscopy. Nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy is a technique that has become available with the development of femtosecond infrared laser pulses. In this experiment, first a set of pump pulses is applied to the sample. This is followed by a waiting time during which the system is allowed to relax. The typical waiting time lasts from zero to several picoseconds, and the duration can be controlled with a resolution of tens of femtoseconds. A probe pulse is then applied, resulting in the emission of a signal from the sample. The nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectrum is a two-dimensional correlation plot of the frequency ω1 that was excited by the initial pump pulses and the frequency ω3 excited by the probe pulse after the waiting time. This allows the observation of coupling between different vibrational modes; because of its extremely fine time resolution, it can be used to monitor molecular dynamics on a picosecond timescale. It is still a largely unexplored technique and is becoming increasingly popular for fundamental research.

As with two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (2DNMR) spectroscopy, this technique spreads the spectrum in two dimensions and allows for the observation of cross peaks that contain information on the coupling between different modes. In contrast to 2DNMR, nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy also involves the excitation to overtones. These excitations result in excited state absorption peaks located below the diagonal and cross peaks. In 2DNMR, two distinct techniques, COSY and NOESY, are frequently used. The cross peaks in the first are related to the scalar coupling, while in the latter they are related to the spin transfer between different nuclei. In nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy, analogs have been drawn to these 2DNMR techniques. Nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy with zero waiting time corresponds to COSY, and nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy with finite waiting time allowing vibrational population transfer corresponds to NOESY. The COSY variant of nonlinear two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy has been used for determination of the secondary structure content of proteins.[50]

See also

edit- Applied spectroscopy

- Astrochemistry

- Atomic and molecular astrophysics

- Atomic force microscopy based infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR)

- Cosmochemistry

- Far-infrared astronomy

- Forensic chemistry

- Forensic engineering

- Forensic polymer engineering

- Infrared astronomy

- Infrared microscopy

- Infrared multiphoton dissociation

- Infrared photodissociation spectroscopy

- Infrared spectroscopy correlation table

- Infrared spectroscopy of metal carbonyls

- Near-infrared spectroscopy

- Nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy

- Photothermal microspectroscopy

- Raman spectroscopy

- Rotational-vibrational spectroscopy

- Time-resolved spectroscopy

- Vibrational spectroscopy of linear molecules

References

edit- ^ Zeitler JA, Taday PF, Newnham DA, Pepper M, Gordon KC, Rades T (February 2007). "Terahertz pulsed spectroscopy and imaging in the pharmaceutical setting--a review". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 59 (2): 209–23. doi:10.1211/jpp.59.2.0008. PMID 17270075. S2CID 34705104.

- ^ "Infrared Spectroscopy". ColourLex. 12 March 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Derrick MR, Stulik D, Landry JM (1999). Infrared Spectroscopy in Conservation Science (PDF). Scientific Tools for Conservation. Getty Publications. ISBN 0-89236-469-6.

- ^ Ricciardi P. "Unlocking the secrets of illuminated manuscripts". Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Lau WS (1999). Infrared characterization for microelectronics. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-2352-6.

- ^ Osborne BG (2006). "Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Food Analysis". Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470027318.a1018. ISBN 9780470027318.

- ^ Villar A, Gorritxategi E, Aranzabe E, Fernández S, Otaduy D, Fernández LA (December 2012). "Low-cost visible-near infrared sensor for on-line monitoring of fat and fatty acids content during the manufacturing process of the milk". Food Chemistry. 135 (4): 2756–60. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.074. PMID 22980869.

- ^ www.TRMThemes.com, TRM Theme by. "Infrared (IR) / Optical Based Archives - Heath Consultants". Heath Consultants. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ Becker, Wolfgang; Sachsenheimer, Kerstin; Klemenz, Melanie (2017). "Detection of Black Plastics in the Middle Infrared Spectrum (MIR) Using Photon Up-Conversion Technique for Polymer Recycling Process". Polymers. 9 (9). MDPI. doi:10.3390/polym9090435. PMC 6418689. PMID 30965736.

- ^ Perry, Tekla S. (2017-03-14). "What Happened When We Took the SCiO Food Analyzer Grocery Shopping". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ^ Coates, John (18 June 2014). "A Review of New Small-Scale Technologies for Near Infrared Measurements". American Pharmaceutical Review. Coates Consulting LLC. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ^ Boosa, Venu; Varimalla, Shirisha; Dumpalapally, Mahesh; Gutta, Naresh; Velisoju, Vijay Kumar; Nama, Narender; Akula, Venugopal (2021-09-05). "Influence of Brønsted acid sites on chemoselective synthesis of pyrrolidones over H-ZSM-5 supported copper catalyst". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 292: 120177. Bibcode:2021AppCB.29220177B. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120177. ISSN 0926-3373.

- ^ Fajdek-Bieda, Anna; Wróblewska, Agnieszka; Miądlicki, Piotr; Tołpa, Jadwiga; Michalkiewicz, Beata (2021-08-01). "Clinoptilolite as a natural, active zeolite catalyst for the chemical transformations of geraniol". Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis. 133 (2): 997–1011. doi:10.1007/s11144-021-02027-3. ISSN 1878-5204. S2CID 236149569.

- ^ Azancot, Lola; Bobadilla, Luis F.; Centeno, Miguel A.; Odriozola, José A. (2021-05-15). "IR spectroscopic insights into the coking-resistance effect of potassium on nickel-based catalyst during dry reforming of methane". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 285: 119822. Bibcode:2021AppCB.28519822A. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119822. hdl:10261/251396. ISSN 0926-3373. S2CID 232627637.

- ^ Nuguid, Rob Jeremiah G.; Elsener, Martin; Ferri, Davide; Kröcher, Oliver (2021-12-05). "Operando diffuse reflectance infrared detection of cyanide intermediate species during the reaction of formaldehyde with ammonia over V2O5/WO3-TiO2". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 298: 120629. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120629. ISSN 0926-3373.

- ^ Sockalingum, G. D.; Bouhedja, W.; Pina, P.; Allouch, P.; Bloy, C.; Manfait, M. (February 1998). "FT-IR spectroscopy as an emerging method for rapid characterization of microorganisms". Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-Le-Grand, France). 44 (1): 261–269. ISSN 0145-5680. PMID 9551657.

- ^ Helm, D.; Labischinski, H.; Schallehn, Gisela; Naumann, D. (1991-01-01). "Classification and identification of bacteria by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy". Microbiology. 137 (1): 69–79. doi:10.1099/00221287-137-1-69. ISSN 1350-0872. PMID 1710644.

- ^ Holt, C; Hirst, D; Sutherland, A; MacDonald, F (January 1995). "Discrimination of species in the genus Listeria by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and canonical variate analysis". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 61 (1): 377–378. Bibcode:1995ApEnM..61..377H. doi:10.1128/aem.61.1.377-378.1995. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 167294. PMID 7887620.

- ^ Campos, Joana; Sousa, Clara; Mourão, Joana; Lopes, João; Antunes, Patrícia; Peixe, Luísa (November 2018). "Discrimination of non-typhoid Salmonella serogroups and serotypes by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: A comprehensive analysis". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 285: 34–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.07.005. PMID 30015261.

- ^ Sharaha, Uraib; Rodriguez-Diaz, Eladio; Sagi, Orli; Riesenberg, Klaris; Salman, Ahmad; Bigio, Irving J.; Huleihel, Mahmoud (July 2019). "Fast and reliable determination of Escherichia coli susceptibility to antibiotics: Infrared microscopy in tandem with machine learning algorithms". Journal of Biophotonics. 12 (7): e201800478. doi:10.1002/jbio.201800478. ISSN 1864-063X. PMID 30916881.

- ^ Wijesinghe, Hewa G. S.; Hare, Dominic J.; Mohamed, Ahmed; Shah, Alok K.; Harris, Patrick N. A.; Hill, Michelle M. (2021). "Detecting antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli using benchtop attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and machine learning". The Analyst. 146 (20): 6211–6219. Bibcode:2021Ana...146.6211W. doi:10.1039/D1AN00546D. ISSN 0003-2654. PMID 34522918.

- ^ Suleiman, Manal; Abu-Aqil, George; Sharaha, Uraib; Riesenberg, Klaris; Lapidot, Itshak; Salman, Ahmad; Huleihel, Mahmoud (June 2022). "Infra-red spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms enables early determination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa's susceptibility to antibiotics". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 274: 121080. Bibcode:2022AcSpA.27421080S. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2022.121080. PMID 35248858.

- ^ "IR Biotyper® for Food Microbiology". www.bruker.com. Retrieved 2024-03-20.

- ^ Silverstein, Robert M.; Webster, Francis X.; Kiemle, David J.; Bryce, David L. (2016). Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 8th Edition. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-61637-6.

- ^ Banwell, Colin N. (1966). Fundamentals of molecular spectroscopy. European chemistry series. London: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-094020-8.

- ^ Atkins P, de Paula J (2002). Physical Chemistry (7th ed.). New York: W.H.Freeman. p. 513. ISBN 0-7167-3539-3.|quote=the electric dipole moment of the molecule must change when the atoms are displaced relative to one another

- ^ Atkins, Peter (1994). Physical Chemistry, 5th Edition. Freeman. p. 577.

- ^ Schrader B (1995). Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy: Methods and Applications. New York: VCH, Weinheim. p. 787. ISBN 978-3-527-26446-9.

- ^ Arnold J. Gordon; Richard A. Ford (1972). TheChemist's Companion. Wiley. p. 179.

- ^ a b Harwood LM, Moody CJ (1989). Experimental organic chemistry: Principles and Practice (Illustrated ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-632-02017-1.

- ^ Shadman S, Rose C, Yalin AP (2016). "Open-path cavity ring-down spectroscopy sensor for atmospheric ammonia". Applied Physics B. 122 (7): 194. Bibcode:2016ApPhB.122..194S. doi:10.1007/s00340-016-6461-5. S2CID 123834102.

- ^ a b Chromatography/Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and its applications, by Robert White, p7

- ^ Pollock, Hubert M; Kazarian, S G (2014). "Microspectroscopy in the Mid-Infrared". In Meyers, Robert A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1002/9780470027318.a5609.pub2. ISBN 9780470027318.

- ^ H M Pollock and D A Smith, The use of near-field probes for vibrational spectroscopy and photothermal imaging, in Handbook of vibrational spectroscopy, J.M. Chalmers and P.R. Griffiths (eds), John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Vol. 2, pp. 1472 - 1492 (2002)

- ^ a b Krivanek OL, Lovejoy TC, Dellby N, Aoki T, Carpenter RW, Rez P, et al. (October 2014). "Vibrational spectroscopy in the electron microscope". Nature. 514 (7521): 209–12. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..209K. doi:10.1038/nature13870. PMID 25297434. S2CID 4467249.

- ^ Idrobo JC, Lupini AR, Feng T, Unocic RR, Walden FS, Gardiner DS, et al. (March 2018). "Temperature Measurement by a Nanoscale Electron Probe Using Energy Gain and Loss Spectroscopy". Physical Review Letters. 120 (9): 095901. Bibcode:2018PhRvL.120i5901I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.095901. PMID 29547334.

- ^ Lagos MJ, Batson PE (July 2018). "Thermometry with Subnanometer Resolution in the Electron Microscope Using the Principle of Detailed Balancing". Nano Letters. 18 (7): 4556–4563. Bibcode:2018NanoL..18.4556L. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b01791. PMID 29874456. S2CID 206748146.

- ^ Hachtel JA, Huang J, Popovs I, Jansone-Popova S, Keum JK, Jakowski J, et al. (February 2019). "Identification of site-specific isotopic labels by vibrational spectroscopy in the electron microscope". Science. 363 (6426): 525–528. Bibcode:2019Sci...363..525H. doi:10.1126/science.aav5845. PMID 30705191.

- ^ Hage FS, Nicholls RJ, Yates JR, McCulloch DG, Lovejoy TC, Dellby N, et al. (June 2018). "Nanoscale momentum-resolved vibrational spectroscopy". Science Advances. 4 (6): eaar7495. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.7495H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar7495. PMC 6018998. PMID 29951584.

- ^ Senga R, Suenaga K, Barone P, Morishita S, Mauri F, Pichler T (September 2019). "Position and momentum mapping of vibrations in graphene nanostructures". Nature. 573 (7773): 247–250. arXiv:1812.08294. Bibcode:2019Natur.573..247S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1477-8. PMID 31406319. S2CID 118999071.

- ^ Lagos MJ, Trügler A, Hohenester U, Batson PE (March 2017). "Mapping vibrational surface and bulk modes in a single nanocube". Nature. 543 (7646): 529–532. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..529L. doi:10.1038/nature21699. PMID 28332537. S2CID 4459728.

- ^ Govyadinov AA, Konečná A, Chuvilin A, Vélez S, Dolado I, Nikitin AY, et al. (July 2017). "Probing low-energy hyperbolic polaritons in van der Waals crystals with an electron microscope". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 95. arXiv:1611.05371. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8...95G. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00056-y. PMC 5522439. PMID 28733660.

- ^ Venkatraman K, Levin BD, March K, Rez P, Crozier PA (2019). "Vibrational spectroscopy at atomic resolution with electron impact scattering". Nature Physics. 15 (12): 1237–1241. arXiv:1812.08895. Bibcode:2019NatPh..15.1237V. doi:10.1038/s41567-019-0675-5. S2CID 119452520.

- ^ Henschel H, Andersson AT, Jespers W, Mehdi Ghahremanpour M, van der Spoel D (May 2020). "Theoretical Infrared Spectra: Quantitative Similarity Measures and Force Fields". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 16 (5): 3307–3315. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00126. PMC 7304875. PMID 32271575.

- ^ a b c Smith JG (2011). "Chapter 13 Mass Spectrometry and Infrared Spectroscopy". In Hodge T, Nemmers D, Klein J (eds.). Organic chemistry (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 463–488. ISBN 978-0-07-337562-5. Archived from the original (Book) on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- ^ Badger R (1934). "A Relation Between Internuclear Distances and Bond Force Constants" (PDF). The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2 (3): 128. Bibcode:1934JChPh...2..128B. doi:10.1063/1.1749433.

- ^ Kohli KK, Davies G, Vinh NQ, West D, Estreicher SK, Gregorkiewicz T, et al. (June 2006). "Isotope dependence of the lifetime of the vibration of oxygen in silicon". Physical Review Letters. 96 (22): 225503. Bibcode:2006PhRvL..96v5503K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.225503. PMID 16803320.

- ^ Hamm P, Lim MH, Hochstrasser RM (1998). "Structure of the amide I band of peptides measured by femtosecond nonlinear-infrared spectroscopy". J. Phys. Chem. B. 102 (31): 6123–6138. doi:10.1021/jp9813286.

- ^ Mukamel S (2000). "Multidimensional femtosecond correlation spectroscopies of electronic and vibrational excitations". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 51 (1): 691–729. Bibcode:2000ARPC...51..691M. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.691. PMID 11031297. S2CID 31230696.

- ^ Demirdöven N, Cheatum CM, Chung HS, Khalil M, Knoester J, Tokmakoff A (June 2004). "Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of antiparallel beta-sheet secondary structure" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (25): 7981–90. doi:10.1021/ja049811j. PMID 15212548.