English art is the body of visual arts made in England. England has Europe's earliest and northernmost ice-age cave art.[1] Prehistoric art in England largely corresponds with art made elsewhere in contemporary Britain, but early medieval Anglo-Saxon art saw the development of a distinctly English style,[2] and English art continued thereafter to have a distinct character. English art made after the formation in 1707 of the Kingdom of Great Britain may be regarded in most respects simultaneously as art of the United Kingdom.

Medieval English painting, mainly religious, had a strong national tradition and was influential in Europe.[3] The English Reformation, which was antipathetic to art, not only brought this tradition to an abrupt stop but resulted in the destruction of almost all wall-paintings.[4][5] Only illuminated manuscripts now survive in good numbers.[6]

There is in the art of the English Renaissance a strong interest in portraiture, and the portrait miniature was more popular in England than anywhere else.[7] English Renaissance sculpture was mainly architectural and for monumental tombs.[8] Interest in English landscape painting had begun to develop by the time of the 1707 Act of Union.[9]

Substantive definitions of English art have been attempted by, among others, art scholar Nikolaus Pevsner (in his 1956 book The Englishness of English Art),[10] art historian Roy Strong (in his 2000 book The Spirit of Britain: A narrative history of the arts)[11] and critic Peter Ackroyd (in his 2002 book Albion).[12]

Earliest art

editThe earliest English art – also Europe's earliest and northernmost cave art – is located at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire, estimated at between 13,000 and 15,000 years old.[13] In 2003, more than 80 engravings and bas-reliefs, depicting deer, bison, horses, and what may be birds or bird-headed people were found there. The famous, large ritual landscape of Stonehenge dates from the Neolithic period; around 2600 BC.[14] From around 2150 BC, the Beaker people learned how to make bronze, and used both tin and gold. They became skilled in metal refining and their works of art, placed in graves or sacrificial pits have survived.[15] In the Iron Age, a new art style arrived as Celtic culture and spread across the British isles. Though metalwork, especially gold ornaments, was still important, stone and most likely wood were also used.[16] This style continued into the Roman period, beginning in the 1st century BC, and found a renaissance in the Medieval period. The arrival of the Romans brought the Classical style of which many monuments have survived, especially funerary monuments, statues and busts. They also brought glasswork and mosaics.[17] In the 4th century, a new element was introduced as the first Christian art was made in Britain. Several mosaics with Christian symbols and pictures have been preserved.[18] England boasts some remarkable prehistoric hill figures; a famous example is the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire, which "for more than 3,000 years ... has been jealously guarded as a masterpiece of minimalist art."[19]

Earliest art: gallery

edit-

Ochre horse illustration from the Creswell Crags; 11000-13000 BC.[20]

-

Stonehenge; 2600 BC.[21]

-

Winchester Hoard items; 75-25 BC.[23]

-

Hinton St Mary Mosaic; 4th century AD.[24]

Medieval art

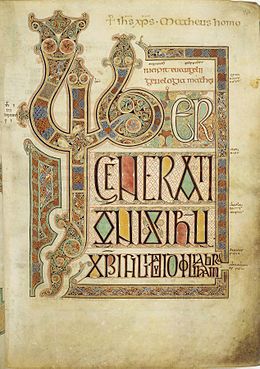

editAfter Roman rule, Anglo-Saxon art brought the incorporation of Germanic traditions, as may be seen in the metalwork of Sutton Hoo.[25] Anglo-Saxon sculpture was outstanding for its time, at least in the small works in ivory or bone which are almost all that survive.[26] Especially in Northumbria, the Insular art style shared across the British Isles produced the finest work being produced in Europe, until the Viking raids and invasions largely suppressed the movement;[27] the Book of Lindisfarne is one example certainly produced in Northumbria.[28] Anglo-Saxon art developed a very sophisticated variation on contemporary Continental styles, seen especially in metalwork and illuminated manuscripts such as the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold.[29] None of the large-scale Anglo-Saxon paintings and sculptures that we know existed have survived.[30]

By the first half of the 11th century, English art benefited from lavish patronage by a wealthy Anglo-Saxon elite, who valued above all works in precious metals.[31] but the Norman Conquest in 1066 brought a sudden halt to this art boom, and instead works were melted down or removed to Normandy.[32] The so-called Bayeux Tapestry - the large, English-made, embroidered cloth depicting events leading up to the Norman conquest - dates to the late 11th century.[33] Some decades after the Norman conquest, manuscript painting in England was soon again among the best of any in Europe; in Romanesque works such as the Winchester Bible and the St. Albans Psalter, and then in early Gothic ones like the Tickhill Psalter.[34] The best-known English illuminator of the period is Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1259).[35] Some of the rare surviving examples of English medieval panel paintings, such as the Westminster Retable and Wilton Diptych, are of the highest quality.[36] From the late 14th century to the early 16th century, England had a considerable industry in Nottingham alabaster reliefs for mid-market altarpieces and small statues, which were exported across Northern Europe.[37] Another art form introduced through the church was stained glass, which was also adopted for secular uses.[38]

Medieval art: gallery

edit-

Sutton Hoo helmet; c. 625.[39]

-

Lindisfarne Gospels; c. 700.[40]

-

Lichfield Gospels; c. 730.[41]

-

The Queen Mary Psalter; 1310–1320.[47]

-

Gorleston Psalter; 14th century.[49]

-

Tickhill Psalter; 14th century.[50]

16th and 17th centuries

editNicholas Hilliard (c. 1547–7 January 1619) – "the first native-born genius of English painting"[54] – began a strong English tradition in the portrait miniature.[55] The tradition was continued by Hilliard's pupil Isaac Oliver (c. 1565–bur. 2 October 1617), whose French Huguenot parents had escaped to England in the artist's childhood.

Other notable English artists across the period include: Nathaniel Bacon (1585–1627); John Bettes the Elder (active c. 1531–1570) and John Bettes the Younger (died 1616); George Gower (c. 1540–1596), William Larkin (early 1580s–1619), and Robert Peake the Elder (c. 1551–1619).[56] The artists of the Tudor court and their successors until the early 18th century included a number of influential imported talents: Hans Holbein the Younger, Anthony van Dyck, Peter Paul Rubens, Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia, Sir Peter Lely (a naturalised English subject from 1662), and Sir Godfrey Kneller (a naturalised English subject by the time of his 1691 knighthood).[57]

The 17th century saw a number of significant English painters of full-size portraits, most notably William Dobson 1611 (bapt. 1611–bur. 1646); others include Cornelius Johnson (bapt. 1593–bur. 1661)[58] and Robert Walker (1599–1658). Samuel Cooper (1609–1672) was an accomplished miniaturist in Hilliard's tradition, as was his brother Alexander Cooper (1609–1660), and their uncle, John Hoskins (1589/1590–1664). Other notable portraitists of the period include: Thomas Flatman (1635–1688), Richard Gibson (1615–1690), the dissolute John Greenhill (c. 1644–1676), John Riley (1646–1691), and John Michael Wright (1617–1694). Francis Barlow (c. 1626–1704) is known as "the father of British sporting painting";[59] he was England's first wildlife painter, beginning a tradition that reached a high-point a century later, in the work of George Stubbs (1724–1806).[60] English women began painting professionally in the 17th century; notable examples include Joan Carlile (c. 1606–79), and Mary Beale (née Cradock; 1633–1699).[61]

In the first half of the 17th century the English nobility became important collectors of European art, led by King Charles I and Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel.[62] By the end of the 17th century, the Grand Tour – a trip of Europe giving exposure to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance – was de rigueur for wealthy young Englishmen.[63]

16th and 17th centuries: gallery

edit-

Nicholas Hilliard's Young Man Among Roses; 1587.[67]

-

Isaac Oliver's A Young Man Seated Under a Tree; 1590–1595.[68]

-

Francis Barlow's Coursing the Hare; 1686.[77]

18th and 19th centuries

editIn the 18th century, English painting's distinct style and tradition continued to concentrate frequently on portraiture, but interest in landscapes increased, and a new focus was placed on history painting, which was regarded as the highest of the hierarchy of genres,[79] and is exemplified in the extraordinary work of Sir James Thornhill (1675/1676–1734). History painter Robert Streater (1621–1679) was highly thought of in his time.[80]

William Hogarth (1697–1764) reflected the burgeoning English middle-class temperament — English in habits, disposition, and temperament, as well as by birth. His satirical works, full of black humour, point out to contemporary society the deformities, weaknesses and vices of London life. Hogarth's influence can be found in the distinctively English satirical tradition continued by James Gillray (1756–1815), and George Cruikshank (1792–1878).[81] One of the genres in which Hogarth worked was the conversation piece, a form in which certain of his contemporaries also excelled: Joseph Highmore (1692–1780), Francis Hayman (1708–1776), and Arthur Devis (1712–1787).[82]

Portraits were in England, as in Europe, the easiest and most profitable way for an artist to make a living, and the English tradition continued to show the relaxed elegance of the portrait-style traceable to Van Dyck. The leading portraitists are: Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788); Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), founder of the Royal Academy of Arts; George Romney (1734–1802); Lemuel "Francis" Abbott (1760/61–1802); Richard Westall (1765–1836); Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830); and Thomas Phillips (1770–1845). Also of note are Jonathan Richardson (1667–1745) and his pupil (and defiant son-in-law) Thomas Hudson (1701–1779). Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797) was well known for his candlelight pictures; George Stubbs (1724–1806) and, later, Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873) for their animal paintings. By the end of the century, the English swagger portrait was much admired abroad.[83]

London's William Blake (1757–1827) produced a diverse and visionary body of work defying straightforward classification; critic Jonathan Jones regards him as "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[84] Blake's artist friends included neoclassicist John Flaxman (1755–1826), and Thomas Stothard (1755–1834) with whom Blake quarrelled.

In the popular imagination English landscape painting from the 18th century onwards typifies English art, inspired largely from the love of the pastoral and mirroring as it does the development of larger country houses set in a pastoral rural landscape.[85] Two English Romantics are largely responsible for raising the status of landscape painting worldwide: John Constable (1776–1837) and J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), who is credited with elevating landscape painting to an eminence rivalling history painting.[86][87] Other notable 18th and 19th century landscape painters include: George Arnald (1763–1841); John Linnell (1792–1882), a rival to Constable in his time; George Morland (1763–1804), who developed on Francis Barlow's tradition of animal and rustic painting; Samuel Palmer (1805–1881); Paul Sandby (1731–1809), who is recognised as the father of English watercolour painting;[88] and subsequent watercolourists John Robert Cozens (1752–1797), Turner's friend Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), and Thomas Heaphy (1775–1835).[89]

The early 19th century saw the emergence of the Norwich school of painters, the first provincial art movement outside of London. Short-lived owing to sparse patronage and internal dissent, its prominent members were "founding father" John Crome (1768–1821), John Sell Cotman (1782–1842), James Stark (1794–1859), and Joseph Stannard (1797–1830).[90]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood movement, established in the 1840s, dominated English art in the second half of the 19th century. Its members — William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), John Everett Millais (1828–1896) and others — concentrated on religious, literary, and genre works executed in a colorful and minutely detailed, almost photographic style.[91] Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) shared the Pre-Raphaelites' principles.[92]

Leading English art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century; from the 1850s he championed the Pre-Raphaelites, who were influenced by his ideas.[93] William Morris (1834–1896), founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement, emphasised the value of traditional craft skills which seemed to be in decline in the mass industrial age. His designs, like the work of the Pre-Raphaelite painters with whom he was associated, referred frequently to medieval motifs.[94] English narrative painter William Powell Frith (1819–1909) has been described as the "greatest British painter of the social scene since Hogarth",[95] and painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) became famous for his symbolist work.

The gallant spirit of 19th century English military art helped shape Victorian England's self-image.[96] Notable English military artists include: John Edward Chapman 'Chester' Mathews (1843–1927);[97] Lady Butler (1846–1933);[98] Frank Dadd (1851–1929); Edward Matthew Hale (1852–1924); Charles Edwin Fripp (1854–1906);[99] Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. (1856–1927);[100] Harry Payne (1858–1927);[101] George Delville Rowlandson (1861–1930); and Edgar Alfred Holloway (1870–1941).[102] Thomas Davidson (1842–1919), who specialised in historical naval scenes,[103] incorporated remarkable reproductions of Nelson-related works by Arnald, Westall and Abbott in England's Pride and Glory (1894).[104]

To the end of the 19th century, the art of Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) contributed to the development of Art Nouveau, and suggested, among other things, an interest in the visual art of Japan.[105]

18th and 19th centuries: gallery

edit-

Arthur Devis's "conversation piece" portrait of the East India Company's Robert James and family; 1751.[111]

-

Richard Westall's Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797; 1806.[120]

-

Thomas Stothard's Procession of the Canterbury Pilgrims; 1806–7.[121]

-

George Arnald's The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798; 1825–27.[125]

-

John Constable's The Hay Wain; c. 1821

-

Constable's Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds; c. 1826 version

-

Thomas Davidson's England's Pride and Glory; 1894.[133]

20th century

editImpressionism found a focus in the New English Art Club, founded in 1886.[135] Notable members included Walter Sickert (1860–1942) and Philip Wilson Steer (1860–1942), two English painters with coterminous lives who became influential in the 20th century. Sickert went on to the post-impressionist Camden Town Group, active 1911–1913, and was prominent in the transition to Modernism.[136] Steer's sea and landscape paintings made him a leading Impressionist, but later work displays a more traditional English style, influenced by both Constable and Turner.[137]

Paul Nash (1889–1946) played a key role in the development of Modernism in English art. He was among the most important landscape artists of the first half of the twentieth century, and the artworks he produced during World War I are among the most iconic images of the conflict.[138] Nash attended the Slade School of Art, where the remarkable generation of artists who studied under the influential Henry Tonks (1862–1937) included, too, Harold Gilman (1876–1919), Spencer Gore (1878–1914), David Bomberg (1890–1957), Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), Mark Gertler (1891–1939), and Roger Hilton (1911–1975).

Modernism's most controversial English talent was writer and painter Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957). He co-founded the Vorticist movement in art, and after becoming better known for his writing than his painting in the 1920s and early 1930s he returned to more concentrated work on visual art, with paintings from the 1930s and 1940s constituting some of his best-known work. Walter Sickert called Wyndham Lewis: "the greatest portraitist of this or any other time".[139] Modernist sculpture was exemplified by English artists Henry Moore (1898–1986), well known for his carved marble and larger-scale abstract cast bronze sculptures, and Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), who was a leading figure in the colony of artists who resided in St Ives, Cornwall during World War II.[140]

Lancastrian L. S. Lowry (1887–1976) became famous for his scenes of life in the industrial districts of North West England in the mid-20th century. He developed a distinctive style of painting and is best known for his urban landscapes peopled with human figures often referred to as "matchstick men".[141]

Notable English artists of the mid-20th century and after include: Graham Sutherland (1903–1980); Carel Weight (1908–1997); Ruskin Spear (1911–1990); pop art pioneers Richard Hamilton (1922–2011), Peter Blake (b. 1932), and David Hockney (b. 1937); and op art exemplar Bridget Riley (b. 1931).

Following the development of Postmodernism, English art became in some respect synonymous toward the end of the 20th century with the Turner Prize; the prize, established in 1984 and named with ostensibly credible intentions after J. M. W. Turner, earned for latterday English art a reputation arguably to its detriment.[142] Prize exhibits have included a shark in formaldehyde and a dishevelled bed.[143]

While the Turner Prize establishment satisfied itself with weak conceptual homages to authentic iconoclasts like Duchamp and Manzoni,[144] it spurned original talents such as Beryl Cook (1926–2008).[145] The award ceremony has since 2000 attracted annual demonstrations by the "Stuckists", a group calling for a return to figurative art and aesthetic authenticity. Observing wryly that "the only artist who wouldn't be in danger of winning the Turner Prize is Turner", the Stuckists staged in 2000 a "Real Turner Prize 2000" exhibition, promising (by contrast) "no rubbish".[146]

20th century: gallery

edit-

Philip Wilson Steer's Girls Running, Walberswick Pier; 1888–94.[147]

-

Harold Gilman's Leeds market; c. 1913.[149]

-

Ruskin Spear's Patients waiting Outside a First Aid Post in a Factory; 1942.[155]

-

Carel Weight's Recruit's Progress; 1942.[156]

-

L. S. Lowry's Going to Work; 1959.

21st century

editThe sculptor Antony Gormley (b. 1950) expressed doubts a decade after winning the Turner Prize about his "usefulness to the human race",[161] and work including Another Place (2005) and Event Horizon (2012) has achieved both acclaim and popularity. The pseudo-subversive urban art of Banksy,[162] has been much discussed in the media.[163]

A highly visible and much praised work of public art, seen for a brief period in 2014 was Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, a collaboration between artist Paul Cummins (b. 1977) and theatre designer Tom Piper. The installation at the Tower of London between July and November 2014 commemorated the centenary of the outbreak of World War I; it consisted of 888,246 ceramic red poppies, each intended to represent one British or Colonial serviceman killed in the War.[164]

Leading contemporary printmakers include Norman Ackroyd and Richard Spare.

English art on display

editSee also

editFurther reading

edit- David Bindman (ed.), The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of British Art (London, 1985)

- Joseph Burke, English Art, 1714–1800 (Oxford, 1976)

- William Gaunt, A Concise History of English Painting (London, 1978)

- William Gaunt, The Great Century of British Painting: Hogarth to Turner (London, 1971)

- Nikolaus Pevsner, The Englishness of English Art (London, 1956)

- William Vaughan, British Painting: The Golden Age from Hogarth to Turner (London, 1999)

- Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain, 1530-1790, 4th Edn, 1978, Penguin Books (now Yale History of Art series)

References

edit- ^ "Britain's first nude?". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Western Dark Ages And Medieval Christendom". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The story of the Reformation needs reforming". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm". Tate. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Manuscripts from the 8th to the 15th century". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Medieval And Renaissance Sculpture". Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Edge of darkness". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Nikolaus Pevsner: The Englishness of English Art: 1955". BBC Online. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "That was then..." The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Ackroyd's England". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Prehistory: Arts & Invention". English Heritage. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "World's oldest doodle found on rock". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Why these Bronze Age relics make me jump for joy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Celts: not quite the barbarians history would have us believe". The Observer. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Romans: Arts & Invention". English Heritage. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Jesus, the early years". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Big Brother's logo 'defiles' White Horse". The Observer. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Graffiti disfigured Ice Age cave art". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Stonehenge: not archaeology, but art". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Uffington White Horse (c.1000BC)". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Archaeologists and amateurs agree pact". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Sacred mysteries". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon treasure hoard casts Beowulf and wealthy warriors of Mercia in a new light". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Ivory Carvings in England from Before the Norman Conquest". BBC History. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Insular Art". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Everything is illuminated". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Benedictional of St Aethelwold". British Library. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon art from the 7th century to the Norman conquest". History Today. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Largest Anglo-Saxon hoard in history discovered". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Norman World of Art". History Today. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Campaign to bring the Bayeux Tapestry back to Britain". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Romanesque Art". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Matthew Paris: English artist and historian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "'Rarest' medieval panel painting saved by recycling". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Alabaster Collection". Nottingham Castle. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Object of the week: stained glass". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Savage warrior: Sutton Hoo Helmet". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Revealed: hidden art behind the gospel truth". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "St Chad Gospels". Lichfield Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Towns and a tapestry". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Psalter returns to St Albans Cathedral". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Peterborough Psalter". Fitzwilliam Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "National Gallery unveils England's oldest altarpiece". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Creation of the World, in the 'Flowers of History'". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Detailed record for Royal 2 B VII". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Luttrell Psalter". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "'Virile, if Somewhat Irresponsible' Design: The Marginalia of the Gorleston Psalter". British Library. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Tickhill Psalter". University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A precious stone set in a silver sea: The Wilton Diptych: Andrew Graham-Dixon deciphers the royal message for so long concealed within medieval England's most famous painting". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Consecration of St Thomas Becket as archbishop". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Midlands glazier created this medieval masterpiece". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Simon (1979). British Art. London: The Tate Gallery & The Bodley Head. p. 12. ISBN 0370300343.

- ^ "Small is beautiful". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Gaunt, William (1978). A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 15–56.

- ^ "Paintings". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Cornelius Johnson: Charles I's Forgotten Painter". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Artworks by or after English art, Art UK. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "Monkeys and Dogs Playing: Francis Barlow (1626–1704)". Art UK. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ Gaunt, William (1978). A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 29–56.

- ^ "Charles I art collection reunited for first time in 350 years as Royal Academy relocates works from Van Dyke and Titian". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "The Town & Country Grand Tour". Town and Country Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Would the real Anne Boleyn please come forward?". On the Tudor Trail. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Montrose, Louis (2006). The Subject of Elizabeth: Authority, Gender, and Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 123. ISBN 0226534758.

- ^ "Portraits of Queen Elizabeth The First, Part 2: Portraits 1573-1587". Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "'Young Man Among Roses' by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619)". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "A Young Man Seated Under a Tree, c. 1590-1595". Royal Collection. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Final Years of Elizabeth I's Reign". History Today. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The only true painting of Shakespeare - probably". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Wihl, Gary (1988). Literature and Ethics: Essays Presented to A. E. Malloch. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0773506624.

- ^ "William Dobson: Charles II, 1630 - 1685. King of Scots 1649 - 1685. King of England and Ireland 1660 - 1685 (When Prince of Wales, with a page)". Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "King Charles I at his Trial". National trust. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "John Evelyn". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles II (1630-1685) c.1676". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "John Locke". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Hodnett, Edward (1978). Francis Barlow: The First Master of English Book Illustration. London: Scolar Press. p. 106. ISBN 0859673502.

- ^ "Artist: John Riley, British, 1646-1691; Samuel Pepys". Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Painting history: Manet on a mission". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Sheldonian ceiling restored". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Hogarth, the father of the modern cartoon". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Newman, Gerald (1978). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837. London: Routledge. p. 525. ISBN 0815303963.

- ^ "A Short History of British Portraiture". Royal Society of Portrait Painters. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Blake's heaven". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Constable, Turner, Gainsborough and the Making of Landscape". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (11 October 2007). "The Sunshine Boy". Time. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

At the turn of the 18th century, history painting was the highest purpose art could serve, and Turner would attempt those heights all his life. But his real achievement would be to make landscape the equal of history painting.

- ^ "British Watercolours 1750-1900: The Landscape Genre". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Paul Sandby at Royal Academy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Landscape painting". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Made In England: Norfolk". BBC Online. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Pre-Raphaelite art: the paintings that obsessed the Victorians". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Into the Frame: the Four Loves of Ford Madox Brown by Angela Thirlwell: review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "John Ruskin's marriage: what really happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Who was William Morris? The textile designer and early socialist whose legacy is still felt today". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "William Powell Frith, 1819–1909". Tate. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Artist and Empire review – a captivating look at the colonial times we still live in". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman, 2 September 1898". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Tate Britain to explore - but not celebrate - art and the British Empire". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Battle of Isandlwana, 22 January 1879". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1854". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Harry Payne: Artist". Look and Learn. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Edgar Alfred Holloway - 1870-1941". Canadian Anglo-Boer War Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Nelson's Last Signal at Trafalgar". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "England's Pride and Glory". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Erotic bliss shared by all at Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "History of the Painted Hall". Old Royal Naval College. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Alexander Pope". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "General James Wolfe (1727-1759) as a Young Man". National Trust-Quebec House. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Mr and Mrs Andrews". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Great Works: The James Family (1751) by Arthur Devis". The Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Robert Clive and Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey, 1757". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Stubbs's equine masterpiece puts animal passion into the National". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Warren Hastings". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump". National Gallery. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Emma Hamilton and George Romney". Walker Art Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Horatio Nelson". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Europe: a Prophecy". British Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The Pilgrimage to Canterbury, 1806–7". Tate. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Plumb-pudding in danger - or - State Epicures taking un Petit Souper by Gillray". British Library. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Saluting the R-ts bomb uncovered on his birth day August 12th. 1816". British Museum. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Portrait of Duke of Wellington". Waterloo 200. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian Dress". British Library. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Fighting Temeraire". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Our English Coasts, 1852 ('Strayed Sheep') 1852". Tate. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Oil Painting - The Last of England". Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles Dickens". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "What to say about... John Ruskin". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles George Gordon". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "England's Pride and Glory". Art UK. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman, 1898". National Army Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "New English Art Club". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Walter Richard Sickert: British artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Philip Wilson Steer: British artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Archival Trail: Paul Nash the war artist". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Wyndham Lewis: a monster - and a master of portrait painting". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Why it's time you fell in love with Britain's battered post-war statues". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "LS Lowry at Tate Britain: glimpses of a world beyond". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Not all modern art is trivial buffoonery". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "He's our favourite artist. So why do the galleries hate him so much?". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Art in 2015: forget the Turner prize - this was the year the Old Masters became sexy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Beryl Cook". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Stuck on the Turner Prize". Artnet. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Girls Running, Walberswick Pier; 1888–94". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Spencer GoreInez and Taki; 1910". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Harold Gilman: Leeds Market, c.1913". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Brighton Pierrots; 1915". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Mark Gertler: Merry-Go-Round, 1916". Tate. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "We are Making a New World". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Sappers at Work: Canadian Tunnelling Company, R14, St Eloi". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A Battery Shelled". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Patients waiting outside a first aid post in a factory". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Recruit's progress: medical inspection". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Shipbuilding on the Clyde: The Furnaces". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "'World's largest tapestry' at Coventry Cathedral repaired". BBC News. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Four-Square (Walk Through), 1966". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Henry Moore exhibition at Kew is a triumph". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The legacy game: Gormley isn't the first artist to worry about his place in history". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Supposing ... Subversive genius Banksy is actually rubbish". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Britain's best-loved artwork is a Banksy. That's proof of our stupidity". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Blood-swept lands: the story behind the Tower of London poppies tribute". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.