The American wigeon (Mareca americana), also known as the baldpate, is a species of dabbling duck found in North America. Formerly assigned to Anas, this species is classified with the other wigeons in the dabbling duck genus Mareca. It is the New World counterpart of the Eurasian wigeon.

| American wigeon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Mareca |

| Species: | M. americana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mareca americana (Gmelin, JF, 1789)

| |

| |

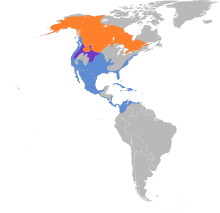

Breeding summer visitor Breeding resident Nonbreeding winter visitor

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anas americana Gmelin, 1789 | |

Taxonomy

editThe American wigeon was formally described in 1789 by German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with all the other ducks, geese, and swans in the genus Anas and coined the binomial name Anas americana.[2] Gmelin based his description on Edme-Louis Daubenton's hand-colour plate of "Le Canard Jensen, de la Louisiane" and Thomas Pennant's description of the "American wigeon" in his Arctic Zoology. Pennant had been sent a specimen from New York.[3][4][5] The American wigeon is now placed with the Eurasian wigeon and three other dabbling ducks in the genus Mareca that was introduced in 1824 by the English naturalist James Francis Stephens.[6][7] The name of the genus comes from the Portuguese word Marréco for a small duck.[8] The species is considered to be monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[7]

An alternative common name is the "baldpate" due to the whitish crown and forehead of the male bird.[9]

Description

editThe American wigeon is a medium-sized bird; it is larger than a teal but smaller than a pintail. In silhouette, the wigeon can be distinguished from other dabblers by its round head, short neck, and small bill.[10] It is 42–59 cm (17–23 in) long, with a 76–91 cm (30–36 in) wingspan and a weight of 512–1,330 g (1.129–2.932 lb).[11][12][13] This wigeon has two adult molts per year and a juvenile molt in the first year, as well.[11]

The breeding male (drake) is a striking bird with a mask of green feathers around its eyes and a cream-colored cap running from the crown of his head to his bill. This white patch gives the wigeon its other common name, baldpate (pate is another word for head).[14] His belly is also white.[15] In flight, drakes can be identified by the large white shoulder patch on each wing. These white patches flash as the birds bank and turn. In nonbreeding (eclipse) plumage, the drake looks more like the female.[10]

The hens are much less conspicuous, having primarily gray and brown plumage. Both sexes have a pale blue bill with a black tip, a white belly, and gray legs and feet.[10] The wing patch behind the speculum is gray. They can be distinguished from most ducks, apart from Eurasian wigeon, by shape. However, that species has a darker head and all-grey underwing. The head and neck coloring of the female is different from the Eurasian wigeon.[15] She nests on the ground, near water and under cover, and lays 6–12 creamy white eggs. Flocks often contain American coots.[11]

The American wigeon is a noisy species, and in the field can often be identified by its distinctive calls. Drakes produce a three-note whistle, while hens emit hoarse grunts and quacks.[10] The male whistle makes a wheezy whoee-whoe-whoe, whereas the female has a low growl qua-ack.

Distribution and habitat

editIt is common and widespread, breeding in all but the extreme north of Canada and Alaska and also in the Interior West through Idaho, Colorado, the Dakotas, and Minnesota, as well as eastern Washington and Oregon.[11][15] The conservation status of this bird is least concern.[1] The majority of the population breeds on wetlands in the Boreal Forest and subarctic river deltas of Canada and Alaska. Although wigeons are found in each flyway, they are most numerous in the Pacific Flyway. Key wintering areas here include the Central Valley of California and Washington's Puget Sound. Farther east, the Texas Panhandle, the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas, and the Caribbean also support large numbers of wintering wigeons.[10]

This dabbling duck is migratory and winters farther south than its breeding range, in the southern half of the United States, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and the Mid-Atlantic coastal region,[11][15] and further south into Central America, the Caribbean, and northwestern South America.[16] It is a rare but regular vagrant to western Europe,[11] and has been observed in significant numbers in Great Britain and Ireland since at least 1958.[17] In the United Kingdom, American wigeons are most commonly observed in autumn and winter.[18]

In 2009, an estimated 2.5 million breeding wigeons were tallied in the traditional survey area—a level just below the 1955–2009 average. In recent decades, wigeon numbers have declined in the Prairie Pothole Region of Canada and increased in the interior and west coast of Alaska. The American wigeon is often the fifth-most commonly harvested duck in the United States, behind the mallard, green-winged teal, gadwall, and wood duck.[10]

Behavior

editThe American wigeon is a bird of open wetlands, such as wet grassland or marshes with some taller vegetation, and usually feeds by dabbling for plant food or grazing, which it does very readily. While on the water, wigeons often gather with feeding coots and divers and are known to grab pieces of vegetation brought to the surface by diving water birds—so are sometimes called "poacher" or "robber" ducks. Wigeons also commonly feed on dry land, eating waste grain in harvested fields and grazing on pasture grasses, winter wheat, clover, and lettuce. Having a largely vegetarian diet, most wigeons migrate in the fall well before northern marshes begin to freeze.[10] The American wigeon is highly gregarious outside of the breeding season and forms large flocks.[11]

Breeding

editBreeding begins in April-May. The nest is a depression on dry ground, often some distance from water. It is lined with grass and down and is hidden in vegetation. The clutch is 7–9, cream-colored eggs, which measure on average 52.9 mm × 37.5 mm (2.08 in × 1.48 in) and weigh 43 g (1.5 oz). They are incubated for 23–25 days by the female only. The male usually deserts the female before the end of the incubation period. The young are precocial and leave the nest within 24 hours of hatching. They can feed themselves. The young can fly when around 47 days of age.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Mareca americana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22680163A92846924. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22680163A92846924.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 526.

- ^ Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de; Martinet, François-Nicolas; Daubenton, Edme-Louis; Daubenton, Louis-Jean-Marie (1765–1783). "Le canard jensen de Louisiane". Planches Enluminées D'Histoire Naturelle. Vol. 10. Paris: De L'Imprimerie Royale. Plate 955.

- ^ Pennant, Thomas (1785). Arctic Zoology. Vol. 2. London, United Kingdom: Printed by Henry Hughs. pp. 567–568, No. 502.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 463.

- ^ Stephens, James Francis (1824). General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History, by the Late George Shaw. Vol. 12 Part 2. London: Printed for G. Kearsley. p. 130.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2022). "Screamers, ducks, geese & swans". IOC World Bird List Version 12.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b Mini, A.E.; Harrington, E.R.; Rucker, E.; Dugger, B.D.; Mowbray, T.B. (2020). Poole, A.F. (ed.). "American Wigeon (Mareca americana), version 1.0". Birds of the World. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bow.amewig.01. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The American Wigeon". Ducks Unlimited. May–June 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g Floyd, T. (2008). Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America. New York: Harper Collins.

- ^ "American Wigeon". All About Birds.

- ^ Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ "Baldpate | bird". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ a b c d Dunn, J.; Alderfer, J. (2006). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America (5th ed.).

- ^ Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- ^ Votier, Stephen C.; Harrop, Andrew H.J.; Denny, Matthew (January 2003). "A review of the status and identification of American Wigeon in Britain & Ireland". British Birds. 96 (1): 2–22. ISSN 0007-0335.

- ^ Ornithology, British Trust for (2015-04-07). "American Wigeon". BTO - British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

Sources

edit- Harrop, A. (1994). "Field identification of American Wigeon". Birding World. 7: 50–56.

- Jiquet, F. (1999). "Photo forum: Hybrid American Wigeons". Birding World. 12: 247–252.

- Larkin, P. (2000). "Eyelid colour of American Wigeon". British Birds. 93: 39–40.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1988). Waterfowl: an Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-46727-6.

- Olson, Storrs L.; James, Helen F.; Meister, C. A. (1981). "Winter field notes and specimen weights of Cayman Island birds". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 101 (3): 339–346. hdl:10088/6535.

- Votier, S. C.; Harrop, A. H. J.; Denny, M. (2003). "A review of status and identification of American Wigeon in Britain and Ireland". British Birds. 96: 2–22.

- Cox, Cameron; Barry, Jessie. "Aging of American and Eurasian Wigeons in female-type plumages" (PDF). Birding. 37 (2): 156–164. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

External links

edit- American Wigeon Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- American Wigeon - Anas americana - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- "American Wigeon media". Internet Bird Collection.

- American Wigeon photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Anas americana at IUCN Red List maps