Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii is a 1972 concert film directed by Adrian Maben and featuring the English rock group Pink Floyd performing at the ancient Roman amphitheatre in Pompeii, Italy. The band performs a typical live set from the era, but there is no audience beyond the basic film crew. The main footage in and around the amphitheatre was filmed over four days in October 1971, using the band's regular touring equipment, including a mobile 8-track recorder from Paris[2] (before being bumped up to 16-track in post-production).[3] Additional footage filmed in a Paris television studio the following December was added for the original 1972 release. The film was then re-released in 1974 with additional studio material of the band working on The Dark Side of the Moon, and interviews at Abbey Road Studios.

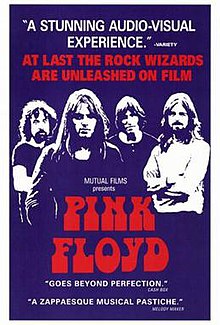

| Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Adrian Maben |

| Starring | Pink Floyd |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by | José Pinheiro |

| Music by | Pink Floyd |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | PolyGram Music Video (1983–1999) Universal Pictures (1999–present) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 64 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

The film has subsequently been released on video numerous times, and in 2002, a Director's cut DVD appeared which combined the original footage from 1971 with more contemporary shots of space and the area around Pompeii, assembled by Maben. A number of bands have taken inspiration from the film in creating their own videos, or filming concerts without an audience.

Background

editFilm-maker Adrian Maben, interested in combining art with Pink Floyd's music,[4] contacted David Gilmour and the band's manager, Steve O'Rourke, in 1971 to discuss the possibilities of making a film in which the band's music was played over images of paintings by René Magritte, Jean Tinguely, Giorgio de Chirico and others. Pink Floyd had experience of filming outside the context of a standard rock concert, including an hour-long performance in KQED TV studios in April 1970;[5] but Maben's idea was rejected. Maben went on holiday to Naples in the early summer.[6] During a visit to Pompeii he lost his passport, and went back to the Amphitheatre, which he had visited earlier in the day, in order to find it. Walking around the deserted ruins, he thought the silence and natural ambient sounds present would make a good backdrop for the music.[6] He also felt that filming the band without an audience would be a good reaction to earlier films such as Woodstock and Gimme Shelter, where the films paid equal attention to performers and spectators.[4] One of Maben's contacts at the University of Naples, Professor Carputi, who was a Pink Floyd fan, managed to persuade the local authorities to close the amphitheatre for six days that October for filming. Access was secured after payment of a "fairly steep" entrance fee.[7]

Filming

editPompeii

editThe performances of "Echoes", "A Saucerful of Secrets", and "One of These Days" were filmed from 4 to 7 October 1971.[8] O'Rourke delivered a demo to Maben in order for him to prepare for the various shots required, which he finally managed to do the night before filming started. The choice of material was primarily the band's, but while Maben realised it was important to include material from the band's new album Meddle, he was also keen to include "Careful with That Axe, Eugene" and "A Saucerful of Secrets", as he felt they would be good numbers to film.[7]

The band insisted on playing live, and brought their regular touring gear with them. Their roadie, Peter Watts, suggested that the 8-track recorder[2] would produce a sound comparable to a studio recording. In addition, the natural echo of the amphitheatre provided good acoustics for the recording.[7] The equipment was carried by truck from London and took three days to reach Pompeii. When it arrived, it was discovered there was insufficient power to drive it correctly.[6] This problem plagued filming for several days, and was finally resolved by running a lengthy cable from the local town hall.[7]

The first section of footage to be filmed were montage shots of the band walking around Boscoreale, mixed with shots of volcanic mud,[4] which can be seen at various points in "Echoes" and "Careful with That Axe, Eugene". For the live performances, the band recorded portions of the songs in sections, which were later spliced together. After each take, they listened to the playback on headphones. Maben closed all the entrances to the amphitheatre, but a few children managed to sneak in and were allowed to watch the filming quietly from a distance.[7]

Paris

editThe remaining songs were filmed in Studio Europasonor, Paris, from 13 to 20 December[4][9] and can be distinguished by the absence of Richard Wright's beard. To fit in with the theme of the earlier work in Pompeii, the filming around Boscoreale, along with stock footage of waterfalls and lava and various shots of Roman mosaics and drawings from the Naples National Archaeological Museum were added into the Paris footage.[10][7] Maben also filmed additional transflex footage for insertion into the Pompeii performances. While both the director and the band were disappointed with this footage, due to a lack of time and money, there was no alternative left but to use it.[7]

During the filming in Paris, the band suggested they would like to film a performance of a short blues song with a howling dog, in the style of "Seamus" from Meddle. Maben knew Madonna Bouglione, daughter of circus director Joseph Bouglione, who was known to walk about Paris with a dog called Nobs. Accordingly, Nobs was invited into the studio, where the footage was filmed for "Mademoiselle Nobs".[7]

Maben subsequently did some of the editing of the final cut at home, due to financial constraints. He regretted doing this, as he felt it was important to separate his work and home life, but, at the time, he had no choice.[11]

Release history

editThe original premiere took place on 2 September 1972, at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.[12] This initial cut, running for one hour, only featured the live footage. The film was scheduled for a special premiere at London's Rainbow Theatre, on 25 November 1972. It was cancelled at the last minute by the theatre's owner, Rank Strand[4] as they didn't have a certificate from the British Board of Film Censors and the theatre could be seen to be in competition with established cinemas.[9]

Maben was concerned that one of the problems with the film was that it was too short.[11] In early 1973, Maben was fly fishing with Waters, and suggested the possibility of improving the film by watching them at work in a recording studio. Subsequently, Maben was invited with a small crew using a single 35 mm camera to Abbey Road Studios to film supposed recording sessions of The Dark Side of the Moon, as well as interviews conducted off-camera by Maben, and footage of the band eating and talking at the studio cafeteria. Maben was particularly happy with this footage, feeling it captured the spontaneous humour of the band.[13]

Running at 80 minutes,[14] this latest version premiered on 10 November 1973, at the Alouette Theatre in Montreal, the release organized in part by George Ritter Films,[15] and Mutual Films.[16] It was a financial success in Canada, and according to Billboard, the film "did such amazing business in its first week in Montreal that the original number of prints ordered for Canada has doubled."[17] The film's American release was overseen by the Cincinnati-based April Fools Films, an independent distributor founded for the purpose of distributing the film.[3] Early test screenings in the US were held in April 1974[18] before premiering in other parts of the country, which happened later into the summer (accompanied in certain instances by a special quadraphonic mix).[3] The film earned considerably more in the US, where, by October 1974, BoxOffice reported that the film had already grossed over $2 million.[3]

The film was not financially successful according to Mason,[19] though Maben disagrees,[7] and suffered particularly from being overshadowed by the release of The Dark Side of the Moon[4] not long after the original theatrical showing. It was released on various home video formats several times.[20]

A director's cut version of the film was released in 2002. It included all the original footage except for the short instrumental intro known as “Pompeii” and the studio footage of “On The Run”, and added some additional filming of the Apollo space program. It also includes the original one-hour cut as a bonus feature.[21] This cut also features approximately 10 minutes of black and white documentary footage shot in 1971 at the Europa-Sonor studio in Paris, and, much like the Abbey Road footage, features shots of the band eating and working in a studio, along with individual interviews.

Unlike the rest of the film, this footage was shot on Maben's own 16mm camera. In 2013, Maben restored and re-edited the footage into a 52-minute documentary titled Chit-Chat with Oysters. The documentary was originally shown at the Toute la mémoire du monde film festival in 2013.[22]

Reception

editMaben was particularly pleased with positive reviews that came out of the film's showing at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, but was disappointed to hear one New York critic describe it "like the size of an ant crawling around the great treasures of Pompeii."[11]

Reviewing the 1974 release, Audience regarded the film as "a handsome visual production."[23] The Hollywood Reporter called it a "fully structured concept which stands on its own quite beyond its function of recording a live rock concert."[24] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three stars out of four and wrote, "The interviews with Pink Floyd are too scattershot to achieve any significance; we are left with the music, which is extremely fine."[25] Meanwhile, Billboard was not enthusiastic about the 1974 release, thinking it looked dated, and stated that the film was "dull, unimaginative and hokey, and does not do justice to the Pink Floyd Vision".[26] Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times dismissed the film as "a fan-magazine article dressed up as a movie, with lots of close-ups of its heroes and an off-screen interviewer who occasionally drops in a question or a comment—about their equipment or their compatibility—and is satisfied with whatever he is told."[27]

However, more recent reviews have been favourable. Billboard reviewed a video release in 1984, and on this occasion, Faye Zuckerman, while not particularly keen on the footage in the Abbey Road canteen, stated it was "vastly superior to most other concert movies".[28] Reviewing the Director's Cut DVD, Richie Unterberger said the film had "first-rate cinematography" and was "undeniably impressive",[29] while Peter Marsh, reviewing for the BBC, stated it was his "favourite concert film of all time", though his opinions of the new computer generated imagery were mixed.[30]

Outtakes

editDue to the lack of time in filming, no tracks were filmed that were unreleased, but several alternative shots and outtakes were held in the Archives du Film du Bois D'Arcy near Paris. At some point, an employee of the owners, MHF Productions, decided this footage was of no value and incinerated all 548 cans of the original 35 mm negatives.[7][11] Maben was particularly frustrated about the lack of additional shots for "One of These Days," which is primarily a Mason solo-piece in the released version.[7] Mason recalls the reason for that is that the reel of film featuring the other members was lost attempting to assemble the original cut.[19]

Track listing

edit1972 original film

edit- "Pompeii"[31]

- "Echoes, Part 1"[32]

- "Careful with That Axe, Eugene"[33]

- "A Saucerful of Secrets"[34]

- "One of These Days"[35]

- "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun"[36]

- "Mademoiselle Nobs"[37]

- "Echoes, Part 2" [38]

1974 theatrical version

edit- "Pompeii"

- "Echoes, Part 1"

- "On the Run" (studio footage)

- "Careful with That Axe, Eugene"

- "A Saucerful of Secrets"

- "Us and Them" (studio footage)

- "One of These Days"

- "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun"

- "Brain Damage" (studio footage)

- "Mademoiselle Nobs"

- "Echoes, Part 2"[39]

2002 DVD

edit- "Echoes, Part 1"

- "Careful with That Axe, Eugene"

- "A Saucerful of Secrets"

- "Us and Them" (studio footage)

- "One of These Days"

- "Mademoiselle Nobs"

- "Brain Damage" (studio footage)

- "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun"

- "Echoes, Part 2"[40]

2016 5.1 Surround Sound film and stereo CD

editThis version is available as part of The Early Years 1965–1972 box set or the smaller 1972: Obfusc/ation set.[41]

- "Careful With That Axe, Eugene"

- "A Saucerful Of Secrets"

- "One of These Days"

- "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun"

- "Echoes"

Credits

editAs shown in the film.[42]

Pink Floyd

- Roger Waters – bass guitar, rhythm guitar on "Mademoiselle Nobs", gong, cymbals, screams and spoken words on "Careful with That Axe, Eugene", lead vocals on "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun", additional piano on "Echoes"

- David Gilmour – lead guitar, slide guitar, harmonica on "Mademoiselle Nobs", lead vocals on "Echoes", vocals on "Careful with That Axe, Eugene" and "A Saucerful of Secrets", additional vocals on "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun"

- Richard Wright – Hammond organ, Farfisa organ, grand piano, lead vocals on "Echoes", VCS 3 on "Pompeii" (intro), dog in ,,Seamus"

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion, vocal phrase on "One of These Days"

Production

- Based on an idea and directed by Adrian Maben

- Cinematography: Willy Kurant, Gábor Pogány

- Camera: Claude Agostini, Jacques Boumendil, Henri Czap, Gérard Hameline

- Sound: Charles Rauchet, Peter Watts

- Script: Marie-Noel Zurstrassen

- Road managers: Chris Adamson, Robert Richardson, Brian Scott

- Production directors: Marc Laurore, Leonardo Pescarolo, Hans Thorner

- Editor: José Pinheiro

- Assistant editor: Marie-Claire Perret

- Mixer: Paul Berthault

- Special effects: Michel François, Michel Y Gouf

- Post production: Auditel, Eclair, Europasonor

- Special thanks to: Professor Carputi (University of Naples), Haroun Tazieff, Soprintendenza alle Antichità della Provincia di Napoli

- Associate producers: Michèle Arnaud, Reiner E. Moritz

- Executive producer: Steve O'Rourke

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[43] | Gold | 5,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[44] | 3× Platinum | 150,000* |

| United States (RIAA)[45] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Legacy

editThe hip hop group the Beastie Boys made a music video for their song "Gratitude" that appears to be a homage to the film. Shot by David Perez in New Zealand,[14] in addition to copying its directorial style of slow horizontal tracking shots, overhead shots of the drums, close up shots of the bass and multiple shots of guitar filling the screen, the video shows a number of speaker cabinets that the group managed to purchase, still labelled "Pink Floyd, London". The video ends with a message that reads, "This video is dedicated to the memory of all the people who died at Pompeii."[46] The Beastie Boys claimed in interviews that the song and the video came about from their desire to progress from being a straightforward hip hop group and add vintage instruments and old sound equipment to their repertoire.[14]

The rock band Korn filmed a similar show, Korn Live: The Encounter, in June 2010 to promote their ninth studio album, Korn III: Remember Who You Are. The show took place in a crop circle in Bakersfield, California, and had no audience beyond the crew workers.[47]

Radiohead were noted for being fans of the film and regularly watched it when on tour.[48] According to bassist Colin Greenwood, his brother Jonny made the whole band watch the film, saying "now this is how we should do videos". Colin, however, was critical of the direction, which he described as "Dave Gilmour sitting on his arse playing guitar and Roger Waters with long greasy hair, sandals and dusty flares, staggers over and picks up this big beater and whacks this gong. Ridiculous."[49]

In July 2016, Gilmour returned to the amphitheatre where the filming took place and performed two live concerts, this time with an audience. While there, he was named an honorary citizen of Pompeii.[50]

References

edit- ^ "Pink Floyd à Pompèi". British Film Institute. London. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ a b Maben, Adrian (March 2013). "Under The Volcano" (p. 80). Mojo. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Hot Combo Draws Trade Attention: Borack, Rehme Into Sales, Establish April Fools Films" (p. 26). International Film Journal. 2 October 1974. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Manning 2006, p. 68.

- ^ Povey 2006, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Blake 2011, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Powell Jr, Paul; Johns, Matt (2003). "Interview with Adrian Maben" (Interview). Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Povey 2006, p. 174.

- ^ a b Povey 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d "In Depth Analysis and interview with Adrian Maben". Brain Damage. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Gibson, John (2 September 1972). 'Space Trip' Set In Pompeii. Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 194.

- ^ a b c "Live at Pompeii: In-Depth Analysis, part one". Brain Damage. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "The Pink Floyd" (p. 71). Billboard. 10 November 1973. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Advertisement (p. 50). Montreal Gazette. 11 November 1973. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Movie Music" (p. 51). Billboard. 24 November 1973. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "'Pink Floyd' Picture Has World Premiere in Cincy" (p. ME-1). BoxOffice. 29 April 1974. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b Mason 2004, p. 177.

- ^ "Pink Floyd – Live at Pompeii [VHS]". Amazon. July 1991. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Marsh, Peter. "Pink Floyd Live at Pompeii DVD Review". BBC Music. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Chit Chat With Oysters (Adrian Maben, 2013) à voir en ligne sur HENRI, la plateforme des collections films de la Cinémathèque française". www.cinematheque.fr (in French). Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Robbeloth, DeWitt (October 1974). "Optical Allusions: Pink Floyd" (p. 10). Audience. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Dorr, John (3 September 1974). Movie Review: Pink Floyd. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Siskel, Gene (August 8, 1974). "'Pink Floyd' and Pompeii". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 6.

- ^ Old British Pink Floyd Flick – Not One Of Season's Best. Billboard. 31 August 1974. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (August 22, 1974). "The Screen: 'Pink Floyd'". The New York Times. p. 27.

- ^ Video Reviews. Billboard. 21 July 1984. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. DVD review at AllMusic. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Marsh, Peter. "BBC Review". BBC Music. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ film, 0:00.

- ^ film, 3:45.

- ^ film, 15:32.

- ^ film, 22:21.

- ^ film, 32:40.

- ^ film, 38:44.

- ^ film, 49:06.

- ^ film, 51:04.

- ^ Pink Floyd - Live At Pompeii (Full Length Version) (Media notes). 4 Front Video. 1994. 080 730 3.

- ^ Pink Floyd : Live at Pompeii. Universal. 2003. 820 131 6.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Detail Massive 27-Disc 'Early Years' Box Set". Rolling Stone. 28 July 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ film, 1:03:39–1:04:41.

- ^ "Canadian video certifications – Pink Floyd – Live At Pompeii". Music Canada. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "British video certifications – Pink Floyd – Live At Pompeii". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "American video certifications – Pink Floyd – Live At Pompeii". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Gratitude: Official music video". EMI. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Korn's Blog". Korn Official MySpace Channel. 8 July 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Pierre Perrone (18 August 2012). "Prog – a genre that still has a firm grip on the British psyche". The Independent. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Interview with Radiohead". Q Magazine. June 1997. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "David Gilmour Returns to Pompeii After 45 Years". Consequence of Sound. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

Sources

edit- Blake, Mark (2011). Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. Arum Press. ISBN 978-1-845-13748-9.

- Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd: The Music and The Mystery. New York City: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- Manning, Toby (2006). The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (1st ed.). New York City: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-575-1.

- Mason, Nick (2004). Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84387-0.

- Povey, Glenn (2007). Echoes: The Complete History of Pink Floyd. Chesham: Mind Head Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5.

- Lunatics, The (2016). Pink Floyd A Pompei – Una Storia Fuori Dal Tempo. Firenze: Giunti. ISBN 9788809832695.

- Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii. Polygram. 790 182 2.