Ketoacidosis is a metabolic state caused by uncontrolled production of ketone bodies that cause a metabolic acidosis. While ketosis refers to any elevation of blood ketones, ketoacidosis is a specific pathologic condition that results in changes in blood pH and requires medical attention. The most common cause of ketoacidosis is diabetic ketoacidosis but it can also be caused by alcohol, medications, toxins, and rarely, starvation.

| Ketoacidosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ketone bodies | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | nausea, vomiting, pain, weakness, unusual breath odor, rapid breathing |

| Causes | medications, alcoholic beverages |

Signs and symptoms

editThe symptoms of ketoacidosis are variable depending on the underlying cause. The most common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and weakness.[1][2] Breath may also develop the smell of acetone as it is a volatile ketone that can be exhaled. Rapid deep breathing, or Kussmaul breathing, may be present to compensate for the metabolic acidosis.[1] Altered mental status is more common in diabetic than alcoholic ketoacidosis.[2]

Causes

edit- Muscle fiber

- Amino acids

- Liver

- Fatty acids

- Glucagon

- Blood vessel

- Lack of insulin leads to the release of amino acids from the muscle fiber.

- Amino acids are released from the muscle fiber, which get converted into glucose in the liver.

- The glucose produced becomes abundant in the bloodstream.

- Fatty acids and glycerol are released from the adipose tissue, which get converted into ketones in the liver.

- Along with the fatty acids and glycerol, the glucose produced from the lack of insulin also gets converted into ketones in the liver.

- The ketones produced become abundant in the bloodstream.

Ketoacidosis is caused by the uncontrolled production of ketone bodies. Usually the production of ketones is carefully controlled by several hormones, most importantly insulin. If the mechanisms that control ketone production fail, ketone levels may become dramatically elevated and cause dangerous changes in physiology such as a metabolic acidosis.[3][4]

Diabetes

editThe most common cause of ketoacidosis is a deficiency of insulin in type 1 diabetes or late-stage type 2 diabetes. This is called diabetic ketoacidosis and is characterized by hyperglycemia, dehydration and metabolic acidosis. Other electrolyte disturbances such as hyperkalemia and hyponatremia may also be present. A lack of insulin in the bloodstream allows unregulated fatty acid release from adipose tissue which increases fatty acid oxidation to acetyl CoA, some of which is diverted to ketogenesis. This raises ketone levels significantly above what is seen in normal physiology.[1]

Alcohol

editAlcoholic ketoacidosis is caused by complex physiology that is usually the result of prolonged and heavy alcohol intake in the setting of poor nutrition. Chronic alcohol use can cause depleted hepatic glycogen stores and ethanol metabolism further impairs gluconeogenesis. This can reduce glucose availability and lead to hypoglycemia and increased reliance on fatty acid and ketone metabolism. An additional stressor such as vomiting or dehydration can cause an increase in counterregulatory hormones such as glucagon, cortisol and growth hormone which may further increase free fatty acid release and ketone production. Ethanol metabolism can also increase blood lactic acid levels which may also contribute to a metabolic acidosis.[2]

Starvation

editStarvation is a rare cause of ketoacidosis, usually instead causing physiologic ketosis without ketoacidosis.[5] Ketoacidosis from starvation most commonly occurs in the setting of an additional metabolic stressor such as pregnancy, lactation, or acute illness.[5][6]

Medications

editCertain medications can also cause elevated ketones, such as SGLT2 inhibitors causing euglycemic ketoacidosis.[7] Overdose of salicylates or isoniazid can also cause ketoacidosis.[4]

Toxins

editKetoacidosis can be the result of ingestion of methanol, ethylene glycol, isopropyl alcohol, and acetone.[4]

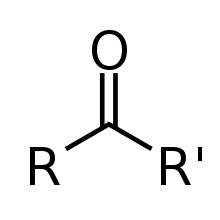

Pathophysiology

editKetones are primarily produced from free fatty acids in the mitochondria of liver cells. The production of ketones is strongly regulated by insulin and an absolute or relative lack of insulin underlies the pathophysiology of ketoacidosis. Insulin is a potent inhibitor of fatty acid release, so insulin deficiency can cause an uncontrolled release of fatty acids from adipose tissue. Insulin deficiency can also enhance ketone production and inhibit peripheral use of ketones.[3] This can occur during states of complete insulin deficiency (such as untreated diabetes) or relative insulin deficiency in states of elevated glucagon and counter-regulatory hormones (such as starvation, heavy chronic alcohol use or illness).[4]

Acetoacetic acid and β-hydroxybutyrate are the most abundant circulating ketone bodies. Ketone bodies are acidic; however, at physiologic concentrations, the body's acid/base buffering system prevents them from changing blood pH.[3]

Management

editTreatment depends on the underlying cause of the ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis is resolved with insulin infusion, intravenous fluids, electrolyte replacement and supportive care.[1] Alcoholic ketoacidosis is treated with intravenous dextrose and supportive care and usually does not require insulin.[2] Starvation ketoacidosis can be resolved with intravenous dextrose with attention to electrolyte changes that can occur with refeeding syndrome.[5]

Epidemiology

editCertain populations are predisposed to develop ketoacidosis including people with diabetes, people with a history of prolonged and heavy alcohol use, pregnant women, breastfeeding women, children, and infants.

People with diabetes that produce very little or no insulin are predisposed to develop ketoacidosis, especially during periods of illness or missed insulin doses. This includes people with type 1 diabetes or ketosis prone diabetes.[1]

Prolonged heavy alcohol use is a risk of ketoacidosis, especially in people with poor nutrition or a concurrent illness.[2]

Pregnant women have high levels of hormones including glucagon and human placental lactogen that increase circulating free fatty acids which increases ketone production.[6] Lactating women also are predisposed to increased ketone production. These populations are at risk of developing ketoacidosis in the setting of metabolic stressors such as fasting, low-carbohydrate diets, or acute illness.[8]

Children and infants have lower glycogen stores and may develop high levels of glucagon and counter-regulatory hormones during acute illness, especially gastrointestinal illness. This allows children and infants to easily produce ketones and although rare, can progress to ketoacidosis in acute illness.[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e Misra, Shivani; Oliver, Nick S (2015-10-28). "Diabetic ketoacidosis in adults". BMJ. 351: h5660. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5660. hdl:10044/1/41091. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 26510442.

- ^ a b c d e McGuire, L. C.; Cruickshank, A. M.; Munro, P. T. (June 2006). "Alcoholic ketoacidosis". Emergency Medicine Journal. 23 (6): 417–420. doi:10.1136/emj.2004.017590. ISSN 1472-0213. PMC 2564331. PMID 16714496.

- ^ a b c Oster, James R.; Epstein, Murray (1984). "Acid-Base Aspects of Ketoacidosis". American Journal of Nephrology. 4 (3): 137–151. doi:10.1159/000166795. ISSN 1421-9670. PMID 6430087.

- ^ a b c d Cartwright, Martina M.; Hajja, Waddah; Al-Khatib, Sofian; Hazeghazam, Maryam; Sreedhar, Dharmashree; Li, Rebecca Na; Wong-McKinstry, Edna; Carlson, Richard W. (October 2012). "Toxigenic and Metabolic Causes of Ketosis and Ketoacidotic Syndromes". Critical Care Clinics. 28 (4): 601–631. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.001.

- ^ a b c Owen, Oliver E.; Caprio, Sonia; Reichard, George A.; Mozzoli, Maria A.; Boden, Guenther; Owen, Rodney S. (July 1983). "Ketosis of starvation: A revisit and new perspectives". Clinics in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 12 (2): 359–379. doi:10.1016/s0300-595x(83)80046-2. ISSN 0300-595X.

- ^ a b Frise, Charlotte J.; Mackillop, Lucy; Joash, Karen; Williamson, Catherine (March 2013). "Starvation ketoacidosis in pregnancy". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 167 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.10.005. ISSN 0301-2115. PMID 23131345.

- ^ Modi, Anar; Agrawal, Abhinav; Morgan, Farah (2017). "Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Review". Current Diabetes Reviews. 13 (3): 315–321. doi:10.2174/1573399812666160421121307. ISSN 1875-6417. PMID 27097605.

- ^ Gleeson, Sarah; Mulroy, Eoin; Clarke, David E. (Spring 2016). "Lactation Ketoacidosis: An Unusual Entity and a Review of the Literature". The Permanente Journal. 20 (2): 71–73. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-097. ISSN 1552-5775. PMC 4867828. PMID 26909776.

- ^ Fukao, Toshiyuki; Mitchell, Grant; Sass, Jörn Oliver; Hori, Tomohiro; Orii, Kenji; Aoyama, Yuka (July 2014). "Ketone body metabolism and its defects". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 37 (4): 541–551. doi:10.1007/s10545-014-9704-9. ISSN 0141-8955. PMID 24706027.

External links

editThe dictionary definition of ketoacidosis at Wiktionary