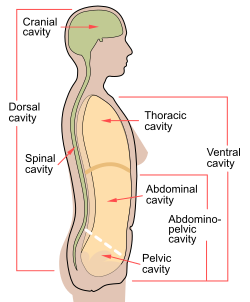

The abdominal cavity is a large body cavity in humans[1] and many other animals that contain organs. It is a part of the abdominopelvic cavity.[2] It is located below the thoracic cavity, and above the pelvic cavity. Its dome-shaped roof is the thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle under the lungs, and its floor is the pelvic inlet, opening into the pelvis.

| Abdominal cavity | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cavitas abdominis |

| MeSH | D034841 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.051 A10.1.00.001 |

| TA2 | 128 |

| FMA | 12266 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure edit

Organs edit

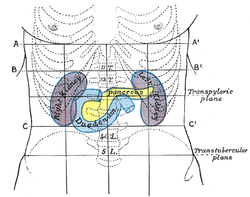

Organs of the abdominal cavity include the stomach, liver, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas, small intestine, kidneys, large intestine, and adrenal glands.[1]

Peritoneum edit

The abdominal cavity is lined with a protective membrane termed the peritoneum. The inside wall is covered by the parietal peritoneum. The kidneys are located behind the peritoneum, in the retroperitoneum, outside the abdominal cavity. The viscera are also covered by visceral peritoneum.

Between the visceral and parietal peritoneum is the peritoneal cavity, which is a potential space.[1] It contains a serous fluid called peritoneal fluid that allows motion. This motion is apparent of the gastrointestinal tract. The peritoneum, by virtue of its connection to the two (parietal and visceral) portions, gives support to the abdominal organs.

The peritoneum divides the cavity into numerous compartments. One of these the lesser sac is located behind the stomach and joins into the greater sac via the foramen of Winslow.[1] Some of the organs are attached to the walls of the abdomen via folds of peritoneum and ligaments, such as the liver and others use broad areas of the peritoneum, such as the pancreas. The peritoneal ligaments are actually dense folds of the peritoneum that are used to connect viscera to viscera or viscera to the walls of the abdomen.[1] They are named in such a way as to show what they connect typically. For example, the gastrocolic ligament connects the stomach and colon and the splenocolic ligament connects the spleen and the colon, or sometimes by their shape as the round ligament or triangular ligament.[1]

Mesentery edit

Mesenteries are folds of peritoneum that are attached to the walls of the abdomen and enclose viscera completely. They are supplied with plentiful amounts of blood. The three most important mesenteries are mesentery for the small intestine, the transverse mesocolon, which attaches the back portion of the colon to the abdominal wall, and the sigmoid mesocolon which enfolds the sigmoid colon.[1]

Omenta edit

The omentum are specialized folds of peritoneum that enclose nerves, blood vessels, lymph channels, fatty tissue, and connective tissue. There are two omenta. First, is the greater omentum that hangs off of the transverse colon and greater curvature of the stomach. The other is the lesser omentum that extends between the stomach and the liver.[1]

Clinical significance edit

Ascites edit

When fluid collects in the abdominal cavity, this condition is called ascites. This is usually not noticeable until enough fluid has collected to distend the abdomen. The collection of fluid will cause pressure on the viscera, veins, and thoracic cavity. Treatment is directed at the cause of the fluid accumulation. One method is to decrease the portal vein pressure, especially useful in treating cirrhosis. Chylous ascites heals best if the lymphatic vessel involved is closed. Heart failure can cause recurring ascites.[1]

Inflammation edit

Another disorder is called peritonitis which usually accompanies inflammatory processes elsewhere. It can be caused by damage to an organ, or from a contusion to the abdominal wall from the outside or by surgery. It may be brought in by the bloodstream or the lymphatic system. The most common origin is the gastrointestinal tract. Peritonitis can be acute or chronic, generalized or localized, and may have one origin or multiple origins. The omenta can help control the spread of infection; however without treatment, the infection will spread throughout the cavity. An abscess may also form as a secondary reaction to an infection. Antibiotics have become an important tool in fighting abscesses; however, external drainage is usually required also.[1]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Abdominal cavity". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak – Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2010. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ Wingerd, Bruce (1994). The Human Body: Concepts of Anatomy and Physiology. Fort Worth: Saunders College Publishing. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-03-055507-8.